Only a few Jewish painters are known from 17th- and 18th-century Amsterdam. In 1637, Samuel d’Orta, ‘Portuguese painter’, bought an etching plate depicting Abraham’s repudiation of Hagar and Ishmael from Rembrandt. D’Orta bought it on condition that Rembrandt himself would not sell any more prints of it. In 1639, Abraham Mendes from Amsterdam was active, but no work by either man is known. Rembrandt’s friend and rival Jan Lievens had two Portuguese-Jewish pupils, Aron de Chavez and Jacob Cardoso Ribero, in 1669. De Chavez left for London in 1674, where he made a painting of Moses and Aaron and the Ten Commandments in 1675. It hung above the ark in the first Portuguese synagogue in that city on Creechurch Lane and is now in the 1701 Bevis Marks synagogue. In the late 17th century the Jacob Carpi arrived from Vernona. Jacob Carpi was active as painter in Amsterdam in the first half of the 18th century.

The Carpi family settled in Amsterdam in the late 17th century. Pater familias was Salomon Carpi. He had at least six children: Abraham, David, Moses, Belitje (Bella), Jacob and Colomba. Colomba married Moses Giron, a bookkeeper on Weesperstraat, in 1694, and Belitje married tobacco buyer Aaron Marsilie in 1698. Both men were from Padua in Italy, close to Venice. Carpi is a town in the province of Modena; Belitje and Colomba’s marriage announcements state that they were ‘from Verona’. No marriage is known of Solomon’s sons. Moses Carpi engaged in trade in precious fabrics and Jacob (also called Jacob da Carpi) was apprenticed to the Dordrecht portrait painter Arnold Boonen, who settled in Amsterdam around the same time. There he probably met young talents like Cornelis Troost and Jacob de Wit, who would later make a name for themselves in Amsterdam. Both would portray Jacob Carpi.

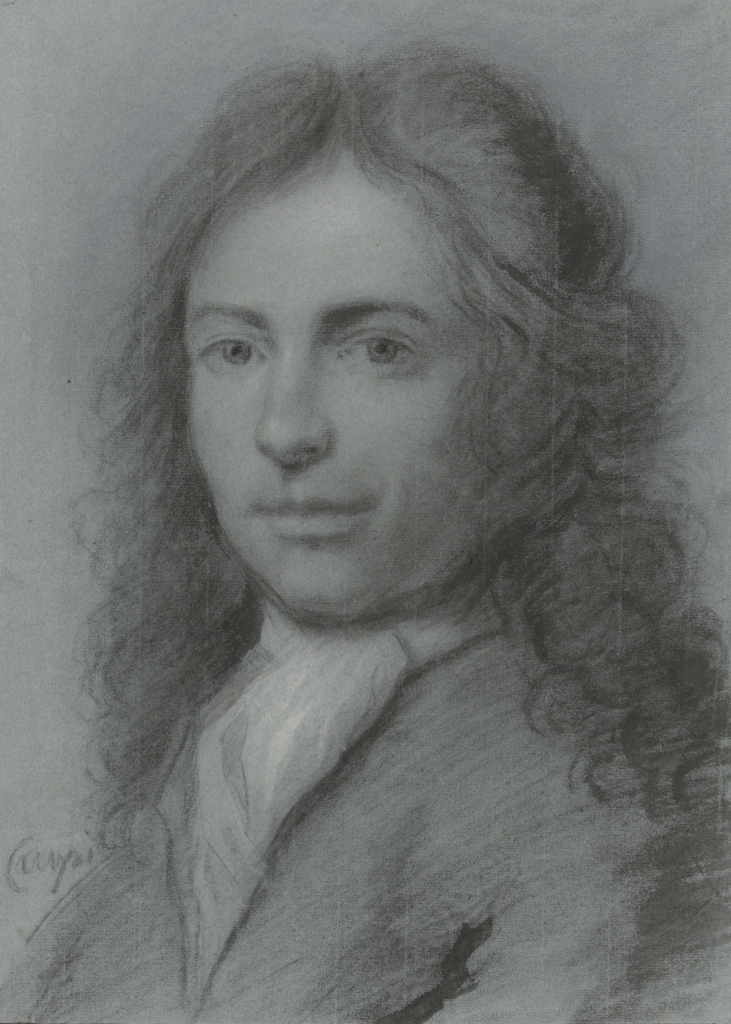

In the Rijksmuseum collection is a beautiful chalk drawing by De Wit of Carpi in the prime of his life, possibly drawn around 1720, and a print by Elisabeth van Woensel after a painting by Cornelis Troost from 1743, showing Carpi sitting on a chair with a pipe in his hand. That painting has been lost, or ended up in an unknown collection. Carpi would continue to call himself a ‘konstschilder’ (art painter) throughout his life, but no works by him are known. A posthumous drawing by Cornelis van Noorde mentions that he painted ‘Pourtraiten, Historien, etc.’, and was a great connoisseur and lover ‘of Papierkonst and Painting’.

As time went on, he concentrated on trading paintings, especially Italian and Flemish masters. Anyone browsing through Amsterdam newspapers of the 18th century regularly comes across a sale by Carpi. On 7 April 1734, the Oudezijds Heerenlogement auctioned ‘a cabinet of paintings, all of the first kind, among which is the renowned ‘Osse-Drift’ by Poulus Potter’, a painting possibly lost in the bombing of Dresden.

In 1737, Carpi valued the paintings in the estate of Maria Agnes Barbou, widow of Joan Occo. In her home at 584 Herengracht, he saw several works by Italian masters such as Raphael, Veronese, Titan and Michelangelo. The most expensive painting was The Adoring Dry Queen by Casper Crayer, estimated at 400 guilders. Carpi also found a ‘Leander’ by Rembrandt there – value 63 guilders, a painting not otherwise described anywhere. It is known that Rembrandt bought a Hero and Leander by Rubens in 1637 and sold it for a profit ten years later. It is possible that he himself made a painting with the same theme.

Financially, Carpi fared well. In 1746, this first generation migrant in Amsterdam bought a house and garden in the Nieuwe Plantage, behind the hortus, at auction for 1500 guilders. Here he not only took up residence and housed his own collection, but also held auctions and art sales. For instance, Carpi advertised in the Amsterdamsche Courant of 24 October 1750 that he had ‘uyt de hand’ all the prints for sale ‘by Raphaël d’Urbino, by Markantoio and Vensesiani’.

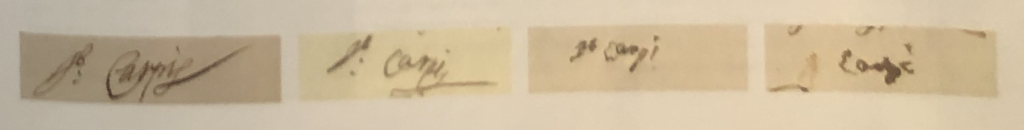

Physically, however, the painter suffered. This is evident from the signatures on several notarial deeds he signed in the last years of his life. When he drew up his will in 1746, he still had a reasonably steady hand, although it was already a lot less convincing that a decade earlier. In 1750, he drew up a new will ‘being somewhat unwell’. It is poignant to see that he apparently could no longer keep his hands still then. Two years later, the handwriting had deteriorated considerably. Was it arthritis? Or could he have had Parkinson’s disease?

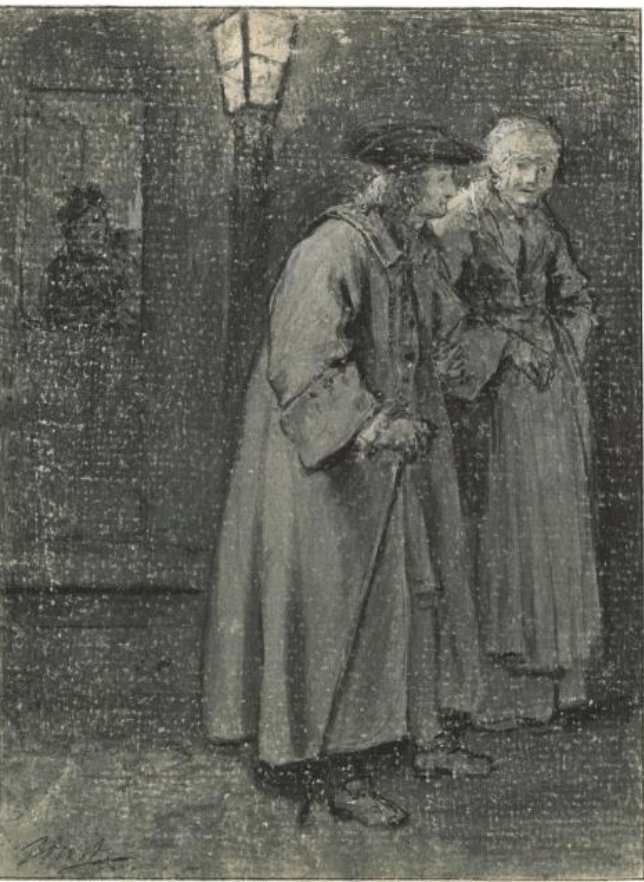

Also in the last phase of his life, Carpi was drawn by Jacob de Wit, as an old frail man walking with a cane, supported by a woman. That will have been his housekeeper Bartha Holmer, whose name we know thanks to the 1750 will. Jacob Carpi was ten years apart from his colleague De Wit; they died shortly after each other. Jacob de Wit was buried in the Oude Kerk (Old Church) on 19 November 1754, aged 59; Jacob Carpi died two and a half months later at the age of 70. On 3 February 1755, he was buried at Beth Haim in Ouderkerk aan de Amstel.

Mark Ponte

Translation of: Mark Ponte, ‘Jacob Carpi, joodse kunstschilder in de 18de eeuw‘, Ons Amsterdam, 1 maart 2023.