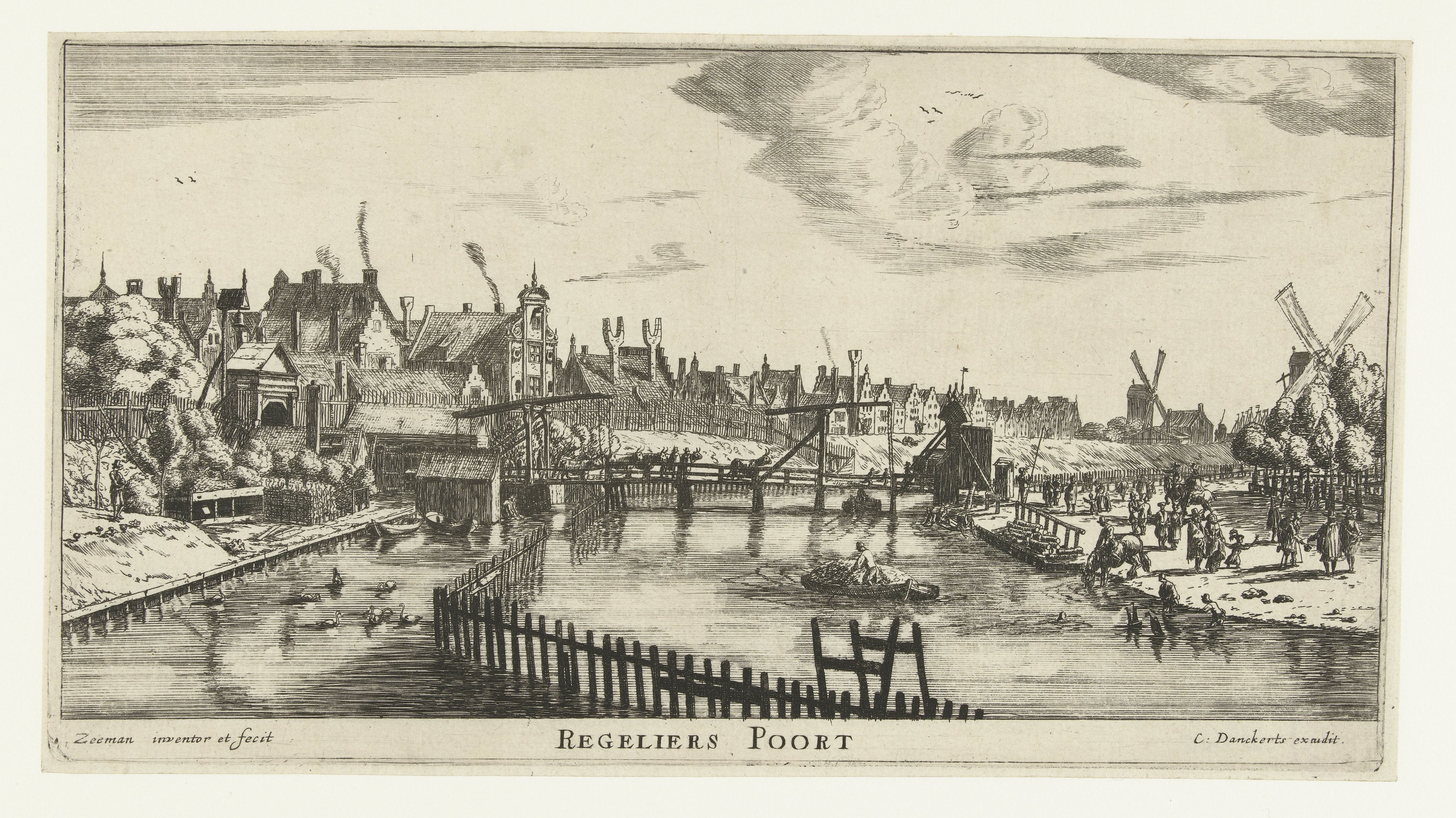

Moroccans in seventeenth century Amsterdam

Translation of ‘Samuel, Mahamet en Hamet’ published in Ons Amsterdam, May 2021.

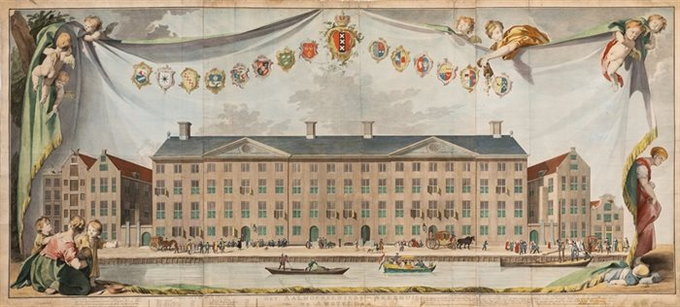

Amsterdam has been a migration city since the sixteenth century. The arrival of Moroccans – now one of the large migrant communities in the city – goes back to the early 17th century.

Many Moroccan migrants who settled in Amsterdam in the 17th century had a Jewish background. The most famous representatives were the Pallache (or Palache) family. They were also literal representatives, for Samuel Pallache (c. 1550-1616), his brother Joseph (c. 1570-1639 or 1649), his sons and his nephew David (1598-1650) acted as emissaries of the kings of Morocco.

Samuel Pallache was born in Fez to a Jewish family from Spain. The Pallaches were true cosmopolitans: they spoke Arabic and Spanish and travelled back and forth between North-Africa and Europe, formally as jewellery traders, but also as diplomats, spies and privateers. In 1605, Samuel Pallache offered his services to the King of Spain as an informer. He and his brother Joseph must have considered converting to Catholicism in order to settle in Spain, but in 1607 they had to leave Spain. They travelled on to the Netherlands and settled in Amsterdam a year later. Their families also made the journey north.

Because of their ties with the Spanish court, the two Pallaches were initially not welcome in the Republic, but Samuel and Joseph managed to be appointed representatives of the Moroccan sultan Muley Zaydan (Zidan Abu Maali, ?-1627), then an ally of the Republic in the conflict with Spain. They played an important role as intermediaries in the relations between the Republic and Morocco and in the liberation of enslaved sailors in North Africa. After Samuel’s death in 1616, Joseph took over the ambassadorship; his son David often acted as his representative.

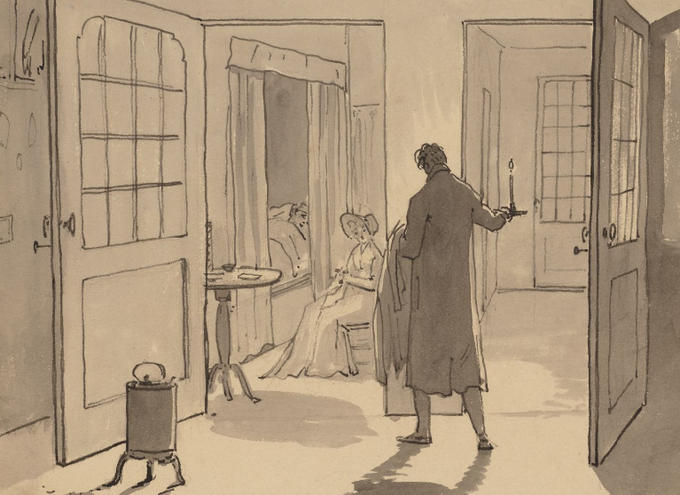

The Pallaches and other North African Jews must have stood out in Amsterdam for their dress, especially their turban, even though the population was diverse in the trading city. All kinds of ‘exotic’ appearances in the street scene inspired Rembrandt and others to make drawings of people in ‘oriental’ attire. A merchant wearing a turban can be seen in paintings of Dam Square.

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Contraband

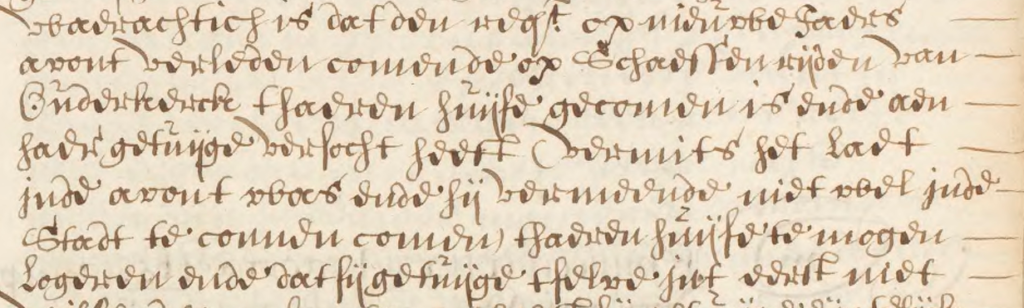

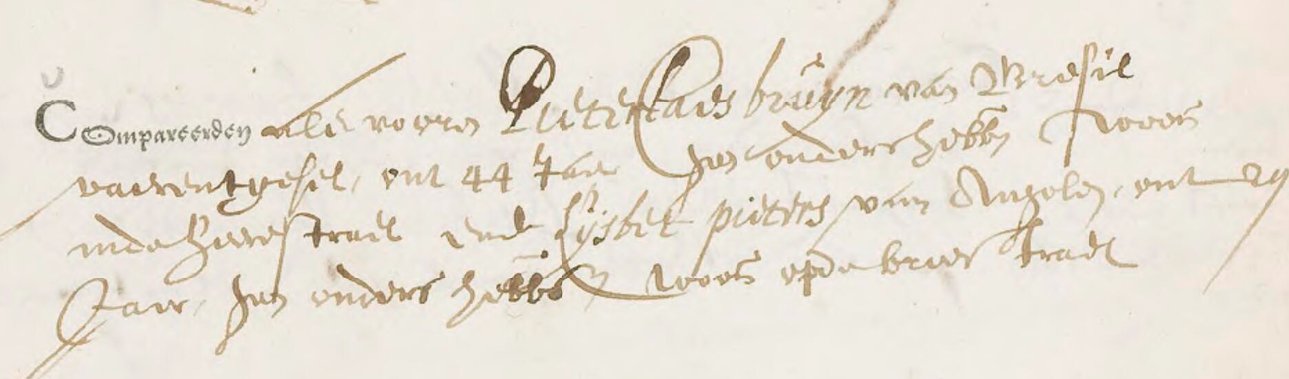

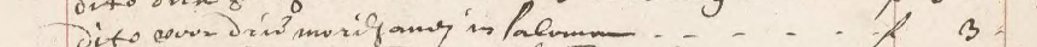

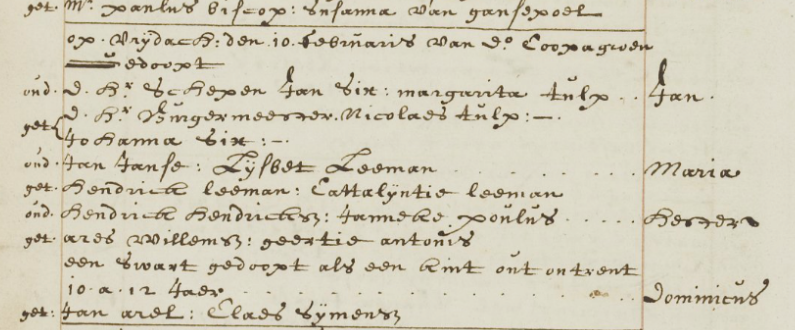

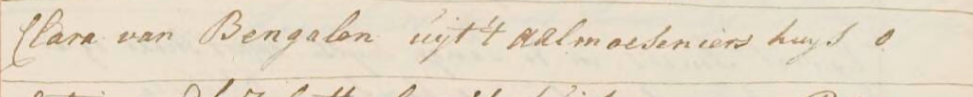

Moroccan immigrants also turn up in the archives of Amsterdam notaries. On 24 December 1672, two Moroccans make a declaration before the notary Dirck van der Groe, Mahamet Benbarck and Hamet Bin Hamet from Salé. Interpreter is the ‘Portuguese merchant’ Joseph Galaco; Galaco was also born in Salé and has a command of the ‘Nederlantse & Moorse spraecke’ (Dutch and ‘Moorish’ language).

Benbarck and Bin Hamet make a statement at the request of the skipper Gerrit Jansz. A few days earlier they had boarded the ship the Koning David, which was to take them to North Africa. The ship lay at anchor on the Rede van Texel, waiting for the skipper, who was still ashore. One Monday, around ten o’clock, the two passengers and almost the entire crew were below deck when they noticed that the ship began to sway and drift.

Mahamet and Hamet rushed upstairs, where they found the helmsman and an axe lying on the ground. Both anchors appeared to be unshackled and the jib unbuttoned. Bin Hamet shouted to the helmsman: “What kind of a helmsman are you, cutting the anchors? Let us go ashore”, to which the helmsman had replied: “Go and eat below”.

Apparently the mate and the ‘hoogbootsman’ Isaack had some nefarious plans. Possibly contraband was involved: according to the Moroccan passengers the mate had “a packet of good in his hand without being able to say what it was”. In any case, the journey was cancelled for the time being. The passengers and crew left the Koning David, after which the ship was left with “only the dog and the cat”.

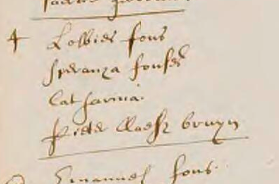

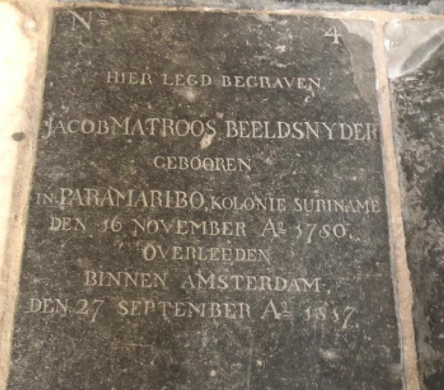

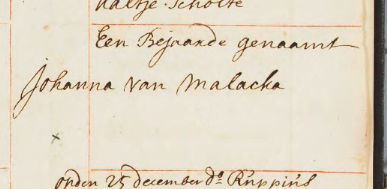

Mahamet Benbarck

Rage

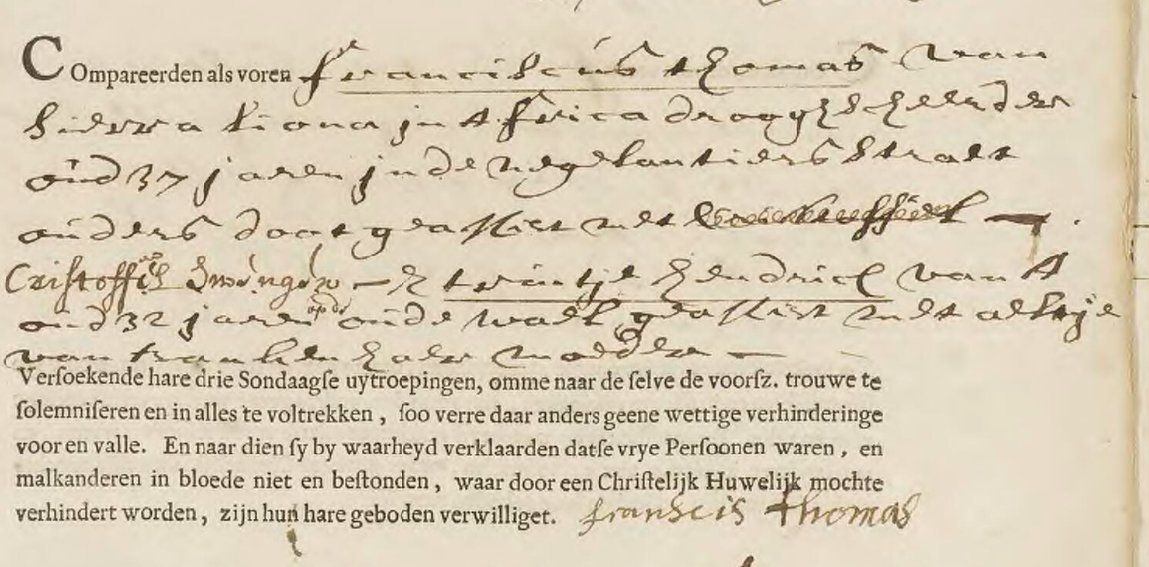

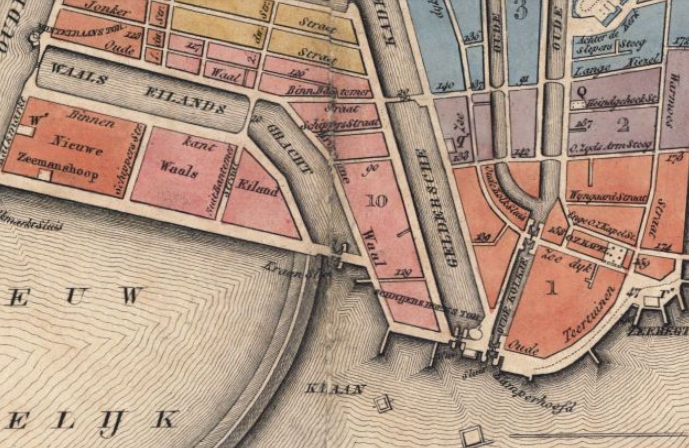

Relations between North African Jews and other Jews were generally good, as were those between North Africans and other Amsterdammers. But there were sometimes tensions in the streets. A confrontation between Samuel Pallache’s nephew David and one ‘Moses Rosado’, in all likelihood Moses Curiel Rosado (1614-1678), is striking. On Monday 2 May 1639 David Pallache was attacked by Rosado in broad daylight on Vlooienburg. While shouting “Oh, Turk!”, Rosado punches him in the face and hits him with a stick and a sabre.

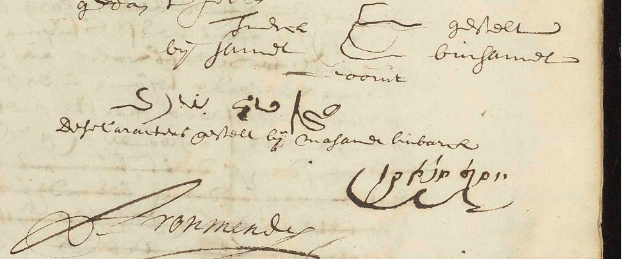

Rosado was arrested and sentenced to two months in the Rasphouse, but a year later he was again the instigator of skirmishes. In June 1640 he assaulted Pallache’s servant in Jodenbreestraat and there was also a confrontation in Ververstraat, during which the servant and Pallache’s nephew fled into a tailor’s shop. Again Moses Rosado is convicted.

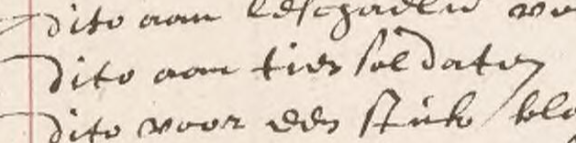

Another Moroccan – “a certain Moor named Achma” – was handcuffed by the sheriff on 20 August 1656, because he had “committed great violence & misconduct on the street”, according to a deed. Achma, apparently drunk, had attacked butcher Thomas Lodewijcksz near the Turfpakhuizen (now: the Academy of Architecture, Waterlooplein). He had pulled Lodewijcksz.’s butcher’s knife from his quiver, “in order to take his life with it”.

It did not come to that: a bystander had come to the butcher’s aid and taken the knife from Achma. Achma moved through the streets, so furious “that everyone fled from him and made a great shouting & roaring noise along the streets, yes so that the people fell over each other and kept lying on the street”. Witnesses mentioned several wounded; Jacob Bueno, at whose request the deed was drawn up, was supposedly beaten so badly that he could hardly stand on his legs and was still in bed a day later.

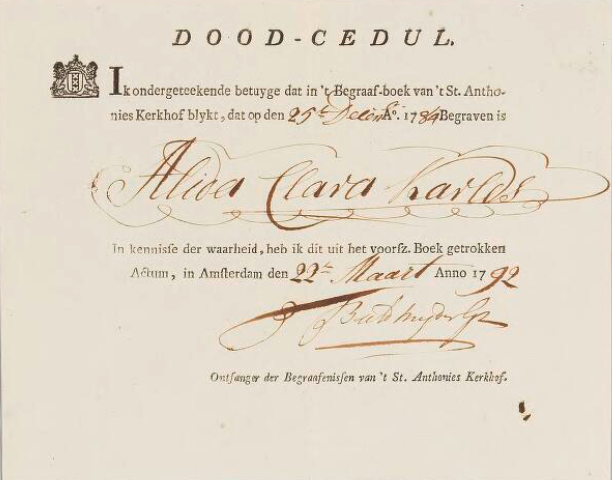

Bueno’s statement may well have been a little exaggerated. The confession book of the sheriff only mentions that the 35-year old Hamet Bar “from Salé in Barbary” had been arrested for the uproar. The notarial document was translated into French for Hamet Bar, but he denied everything and that was the end of it for the authorities. A year later, however, he was arrested again for knife crime. He was clearly not a sweetheart, with his bad temper.