Mark Ponte

Wie beeldmateriaal over de Surinaamse slavernij zoekt komt al snel uit bij de canonieke gravures uit Stedman of de litho’s van Benoit. Foto’s van mensen die in Suriname in slavernij leven zijn zeer schaars. In de film Amsterdam, Sporen van Suiker van Ida Does waren enkele van dit soort foto’s te zien. En natuurlijk zijn er de foto’s uit 1883 in het boek van Bonaparte met onder andere de voormalige slaafgemaakte Jacqueline Ricket en Syntax Bosselman. Jacqueline Ricket werd in slavernij geboren op plantage Paradise, maar was 3 jaar oud en nog ‘spelend’ bij de emancipatie in 1863.

Familie Bosch Reitz met slaafgemaakte bedienden, Paramaribo 1860 (RKD)

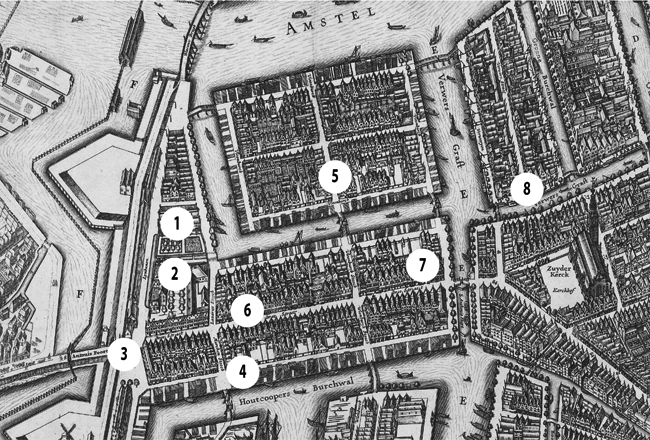

Struinend door de Beeldbank van het RKD stuitte ik enkele jaren geleden op het ‘Portret van Guillaume Jacques Abraham Bosch Reitz (1825-1886) en zijn gezin’. Een bijzondere daguerreotypie uit 1860 van de familie Bosch Reitz in Paramaribo, drie jaar voor de afschaffing van slavernij dus.

Op de foto zien we een typisch tafereel uit de Surinaamse slaventijd. Een witte baby op schoot bij een zwarte slaafgemaakte vrouw met blote voeten. Het was slaafgemaakten niet toegestaan om schoenen te dragen. Links staat een kind van een jaar of acht. De rijke koloniale familie, heeft de zorg en opvoeding van de baby uitbesteed aan slaaf gemaakte vrouwen. Het slaafgemaakte kind links (de ‘futuboi’), staat ieder moment klaar staat om een klusje uit te voeren. De foto werd genomen in het hun prachtige houten huis aan de Waterkant 36 te Paramaribo.

RKD beschrijft de foto als volgt: “Groep in grote kamer. Mevrouw Inniss zittend op grote stoel, waar Guillaume en Josephine achter staan. Guillaume heeft zijn arm om de schouders van zijn vrouw geslagen. Vooraan zit een vrouw met hoofddoek op de grond, met de baby op haar benen. Links staat een kind (bediende?).”

Wie zijn deze mensen? Op de foto staan de Breukelen geboren Guillaume Bosch Reitz (18251880) met zijn vrouw Josephine Gibson Austin (1842-1917) uit Brits-Guyana. Ook Bosch Reitz’ schoonmoeder, Melicent Inniss geboren op het Engels Caribische eiland Barbados, staat op de foto. De baby is Gertrude Elisabeth Sophie Bosch Reitz, geboren in januari 1860. Maar wie zijn de slaafgemaakten op de foto?

Kunnen we deze anonieme mensen die op dat moment in slavernij leefden identificeren? Dat is natuurlijk erg lastig met zekerheid te zeggen. Wel kan je aan de hand van de emancipatieregisters van 1863 en de recent ontsloten slavenregisters een poging wagen.

Toen in 1863 de slavernij in Suriname werd afgeschaft verbleven er vijftien slaafgemaakten bij Guillaume Bosch Reitz. Zij waren afkomstig van verschillende plantages die de familie in handen had. De vrijgemaakten in 1863 waren Julius Babbel (14), Frederika Ellik (45), Andresa Ellik (20), Adriana Falkenstein (80), Jacobus Faré (21), Cornelia Geerberg (60), Juliana Geerberg (16), Adriana Geerberg 5, Clara Giskus (65), Betje Kemnaad (64), Maria Lupson (31), Robert Lupson (15), Frederica Lupson (13), Donderdag Stierbosch (27), Johanneke Betsie (62).

Nou kan er in drie jaar natuurlijk het een en ander veranderd zijn in huize Bosch Reitz, maar het lijkt waarschijnlijk dat deze twee slaafgemaakten ook in 1863 nog bij Bosch Reitz werkten. Zeker de vrouw die voor de kinderen zorgde.

Alleerst het kind dat links staat. Gezien de leeftijden zijn hiervoor eigenlijk maar twee kandidaten, de elfjarige jongen Julius Babbel of het tienjarige meisje Frederica Lupson. De leeftijd van de vrouw die de baby verzorgde, is lastiger te schatten, maar ze lijkt geen zestigplusser en ook geen 18 meer. Ook voor de zittende vrouw zijn er daarom twee kandidaten. Maria Lupson, op dat moment ongeveer 28 jaar oud, en Frederika Ellik die dan 42 zou zijn. Afgaande op de foto lijkt Maria de meest logische kandidaat. Volgens de Surinaamse slavenregisters was Frederica de dochter van Maria. Alles bij elkaar lijkt het mij dan ook zeer waarschijnlijk dat moeder en dochter Maria en Frederica, die in 1863 de achternaam Lupson kregen, hier op de foto staan.

Frederica Lupson (waarschijnlijk), Paramaribo 1860

Maria Lupson (waarschijnlijk), Paramaribo 1860.

Maria en Frederica waren afkomstig van plantage Houttuin. Zij waren tot 1863 in bezit van de Amsterdamse Geertruida Elisabeth Kuvel, echtgenote van Gijsbert Christiaan Bosch Reitz. Alleen al voor plantage Houttuin ontving Kuvel 70.800 gulden compensatie voor het vrijmaken van de slaafgemaakten op 1 juli 1863. Geertruida Elisabeth Kuvel woonde toen de foto gemaakt werd op Keizersgracht 429 in Amsterdam.

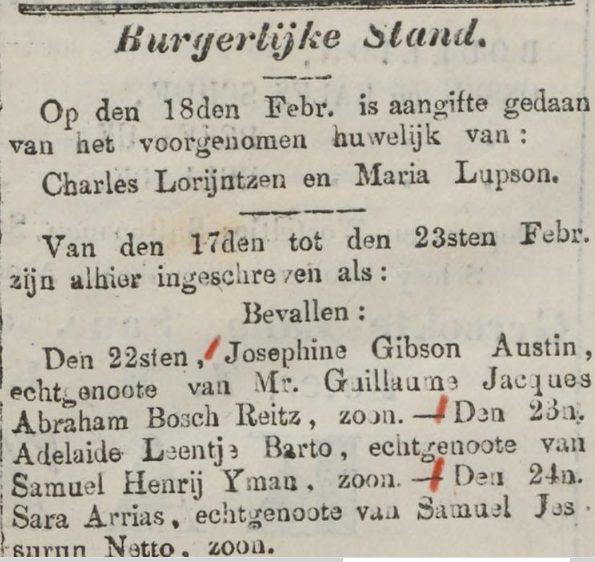

Maria trouwde op 18 februari 1870 met Charles Lorijntzen. Het huwelijk werd aangekondigd in de Surinaamse kranten. Toevalligerwijs (?) werd in diezelfde krant melding gemaakt van de geboorte van een zoon van Guillaume Bosch Reitz. Maria is overleden op 25 februari 1881. Frederica ben ik nog niet tegen gekomen in latere bronnen.

Mark Ponte