Translation of spoken column in 2018. Read the original in Dutch at Over de Muur

We know Rembrandt van Rijn mainly for works such as The Night Watch and The Jewish Bride, but in the course of his career he also painted and drew various black women and men. He was able to do this in his masterly way because he lived in a multicultural seventeenth-century neighbourhood in Amsterdam: the area around today’s Jodenbreestraat, where dozens of people of African descent also lived. People he encountered on the street and could invite to his studio.

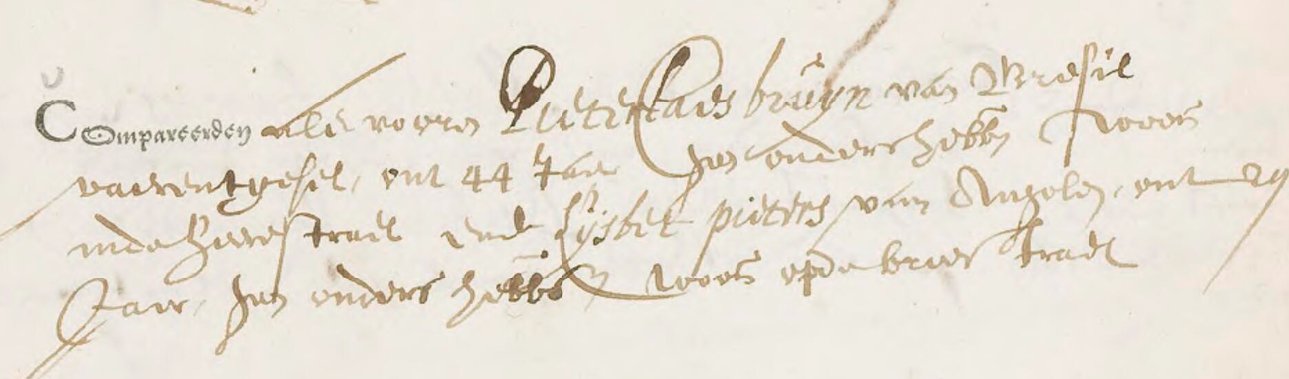

The highlight of Rembrandt’s ‘Black’ oeuvre is of course the painting Two African men – appropriately enough – in the collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague. Appropriate because, like Maurits van Nassau-Siegen, most of the Africans who lived in Rembrandt’s neighbourhood had a history in Dutch Brazil, albeit on a very different rung of the social ladder. Not only did all kinds of returning colonists take enslaved men and women as servants to Amsterdam, but a group of black sailors and soldiers settled here as well. Men who had often been in the service of the West India Company. Some of these sailors knew the entire Atlantic World, from Angola, Brazil and the Caribbean to New Amsterdam, today’s New York.

But not only paintings with black sitters can tell a story about slavery and related themes. Other Rembrandts also lend themselves perfectly to this. Anyone who has visited a bookshop in the Netherlands the past two years will undoubtedly be familiar with the portrait of Jan Six from 1654, which features prominently on the front cover of Geert Mak’s popular book. Whether Six had anything to do with the VOC or WIC I do not know, it could well be that he had shares in that direction.

We know very little about what specific Amsterdammers actually experienced when they went out on the streets, let alone how often someone like Jan Six encountered a black townsman. Did he have friends with black servants in the house?

Jan Six, by Rembrandt (1654),

Collectie Six

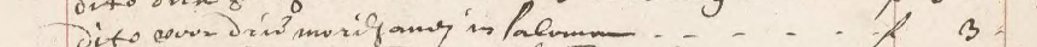

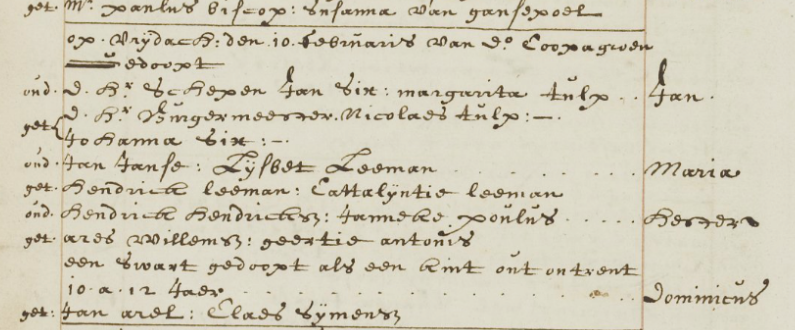

There was at least one important moment when, in the sources, the life of Jan Six crossed that of a young black boy. On Friday 10 February 1668, in the Oude Kerk, in the presence of mayor Nicolaas Tulp, Jan’s son was baptised. Both father Jan Six and grandfather Nicolaas Tulp were painted by Rembrandt, mother Margareta Tulp by Govert Flinck. A chic baptism, therefore, of a member of the highest echelons of the Amsterdam patrician class.

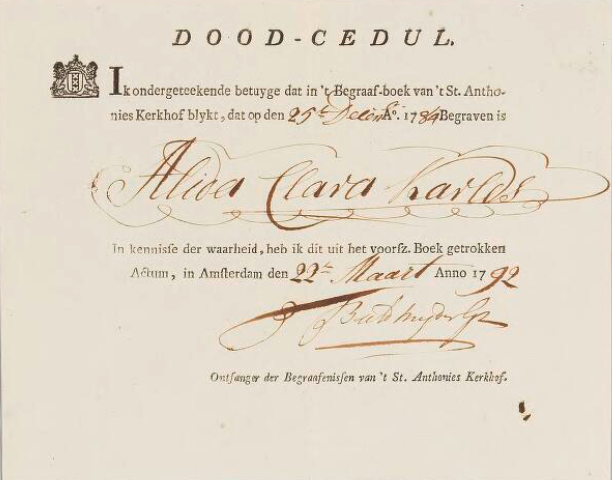

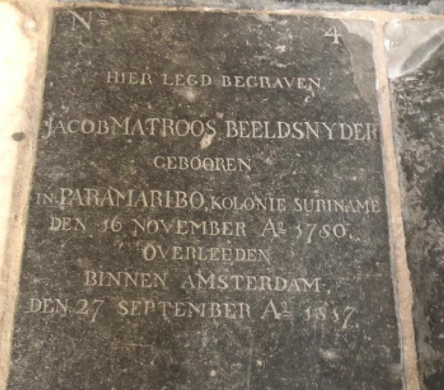

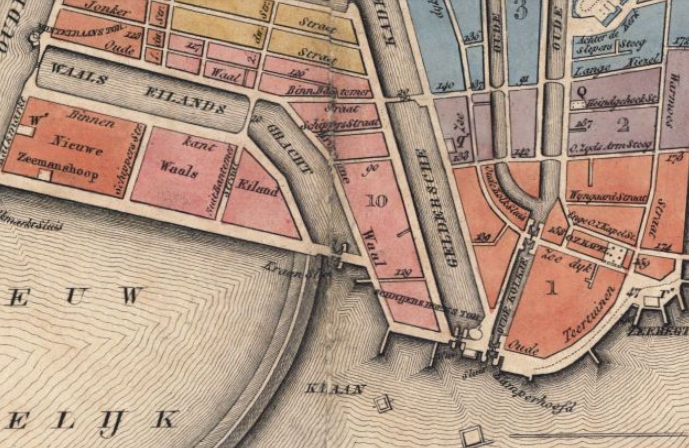

On the same day three other children were baptised, who did not belong to the upper class at all. After Jan the girls Maria and Hester were baptised. The last one to be baptised that day was Dominicus: “A swart [black] about 10 or 12 years of age”, who lived with Claes Philipsoon on Oude Waal; I imagine that Dominicus sat at a distance watching the babies Jan, Maria and Hester being baptised, before it was his turn.

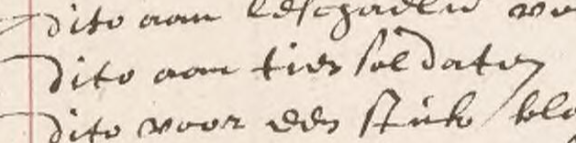

Even the portraits of Marten and Oopjen, the other two Rembrandts, which have received a lot of attention in recent years, can tell several stories that touch on the history of slavery. Marten Soolmans was the son of a wealthy sugar trader and refiner who had settled in Amsterdam after the fall of Antwerp. The relationship between sugar and slavery is not worth explaining here. After the death of Soolmans, Oopjen Coppit remarried to WIC captain and Brazil veteran Maarten Daey.

Portraits of Marten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit, by Rembrand (1634)

Rijksmuseum / Musée du Louvre

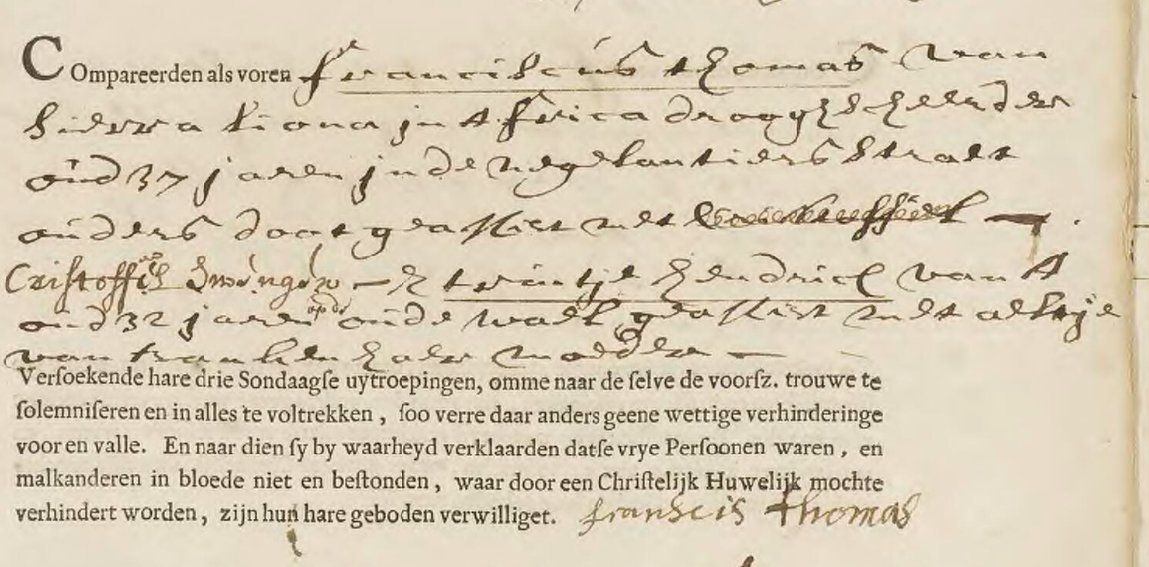

While researching documents about Dutch Brazil, I came across Maarten Daey in a journal of the Reformed Church in Paraiba. In it, the moving story of the black woman Francesca was recorded. Francesca, we read, was captured and locked up in Captain Daey’s house. Francesca was raped by Daey. When it appears that she was pregnant, Daey sent Francesca out of his house, because he wanted nothing to do with the child. Would his son Hendrick Daey, who later owned these two paintings, have known about his Brazilian half-sister Elunam, who was almost twenty years older?

Exhibiton

This is a translation of a spoken column in 2018. The story of Oopjen is now part of the exhibition Slavery. Ten true stories in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.