Niets menselijks was de 17de-eeuwse Amsterdammer vreemd. Dat blijkt uit de Amsterdamse Akten, waar veelvuldig gevallen van overspel zijn opgetekend.

Het notarieel archief van Amsterdam bevat opvallend veel akten over overspel. Het liefdesleven van de gemiddelde Amsterdammer was in vroeger tijden net zo dynamisch als tegenwoordig, maar de officiële en kerkelijke moraal inzake huwelijkse trouw was wel een stuk strenger. Duizenden Amsterdammers stapten naar de notaris om iemand te beschuldigen van overspel, dan wel om zo’n beschuldiging tegen te spreken. Buren en bekenden werden gehoord, meestal op verzoek van de bedrogen partij, om er schande van te spreken.

Lees dit verhaal op de site van Ons Amsterdam of Alle Amsterdamse Akten / Stadsarchief Amsterdam.

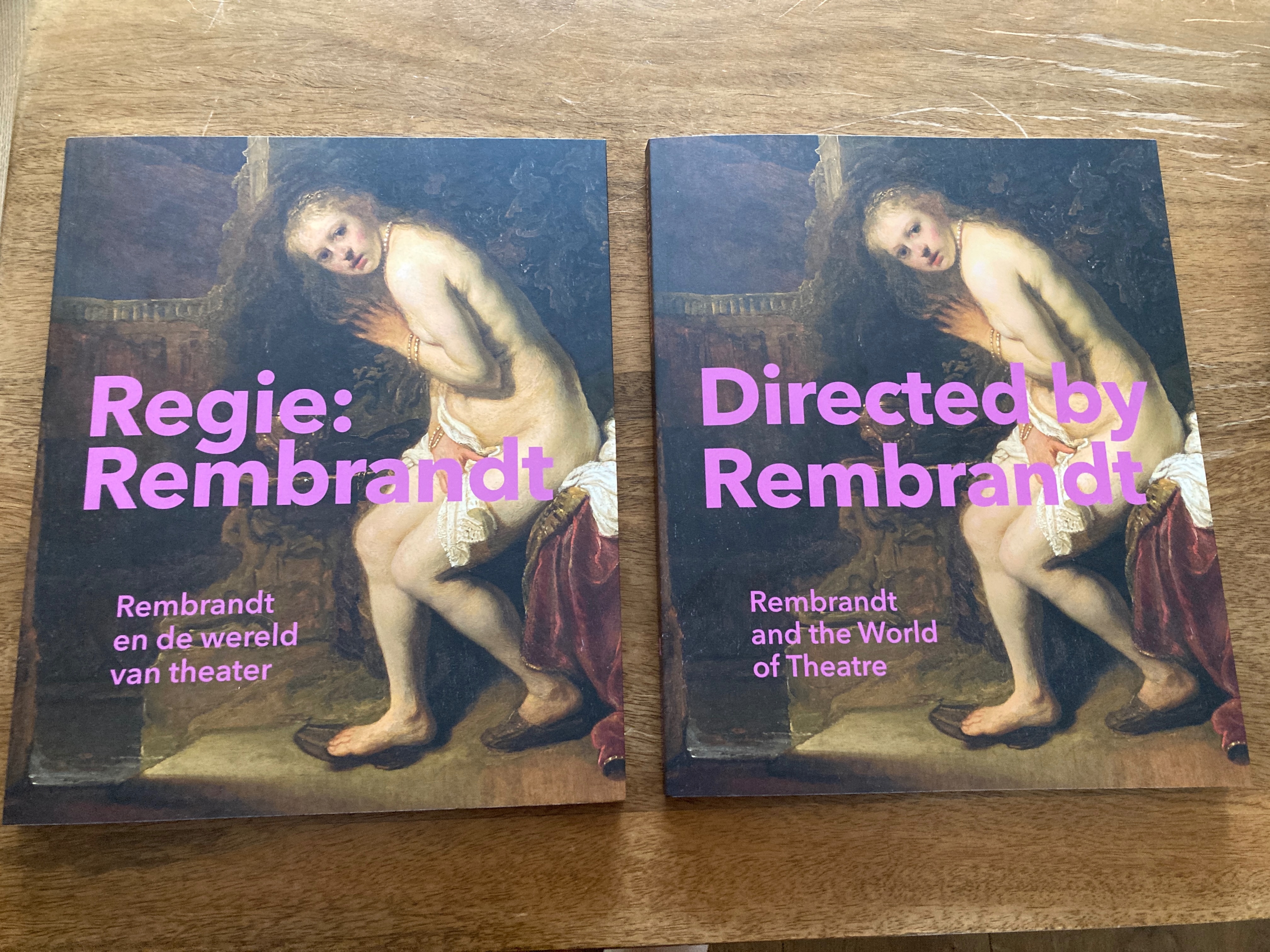

Regie: Rembrandt

Altijd leuk om bij te dragen aan een mooi boek, in dit geval twee korte stukjes voor Regie: Rembrandt, het boek bij de gelijknamige tentoonstelling in het Museum Rembrandthuis. Het ene stukje gaat over een paradijsvogel voor de schouwburg, het andere verhaal over het spelen van ‘de Historie van Hester’ in pakhuizen op en om Vlooienburg. De originele stukken bij mijn stukken zijn nu te zien in het Stadsarchief.

Achter de schermen: Amsterdams theater in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw

Schatkamerpresentatie met werken van o.a. Rembrandt, Reinier Vinkeles en Simon Fokke

Van 2 maart – 26 mei 2024

Gratis toegang

Amsterdamse schouwburg

In 1637 werd aan de Keizersgracht een houten schouwburg gebouwd. Deze plek zou in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw uitgroeien tot dé uitgaansgelegenheid van Amsterdam. Amsterdammers uit alle lagen van de bevolking bezochten het theater, dat een plek van culturele vernieuwing zou blijken. Hier werden gedurende anderhalve eeuw tot de verbeelding sprekende toneelstukken uit heel Europa opgevoerd. Acteurs en vooral actrices werden de sterren van de stad. Het theater vormde bovendien een rijke inspiratiebron voor Rembrandt en zijn leerlingen. Op 11 mei 1772 brandde de schouwburg tot de grond toe af. Een nieuw theater verrees aan het Leidseplein.

In de Schatkamer toont het Stadsarchief een aantal topstukken uit de geschiedenis van de schouwburg, waaronder originele speellijsten. Ook zijn er documenten die uit de brand van 1772 werden gered, zoals een gravure naar Jacob Jordaens.

Theater op straat en in pakhuizen

De presentatie in het Stadsarchief laat ook zien dat niet alleen in de schouwburg theater werd gemaakt. Straattheater was alom aanwezig, zoals op Vlooienburg, het kloppend hart van Joods Amsterdam. Daar werden in pakhuizen en kelders theaterstukken opgevoerd. Het zou goed kunnen dat Rembrandt zich hier liet inspireren voor zijn prent De Triomf van Mordechai, die ook in de Schatkamer tentoongesteld wordt.

Rembrandtplein

Ook op de kermis was straattheater vaste prik: vanaf half september was het in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw altijd druk in de stad. Op de Botermarkt (nu het Rembrandtplein) konden bezoekers koorddansers, acrobaten en straattheater door reizende gezelschappen zien en exotische dieren bewonderen. In een aantal mooie prenten laat de presentatie deze levendige straattaferelen zien.

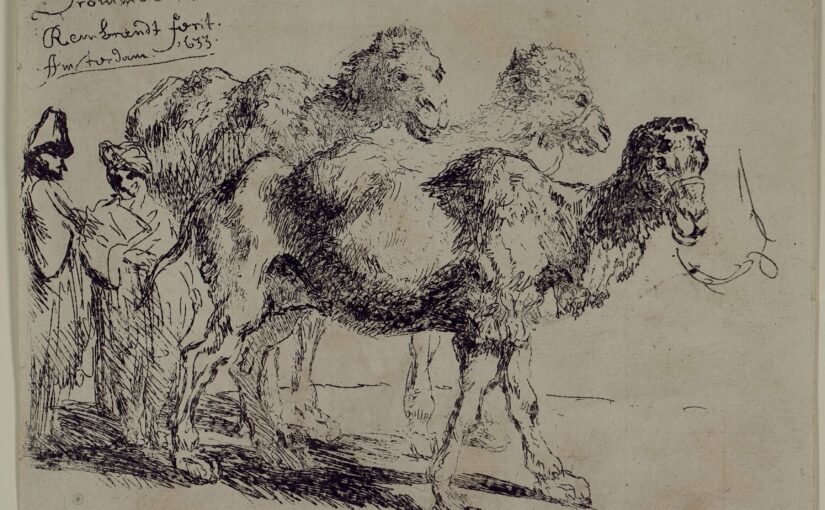

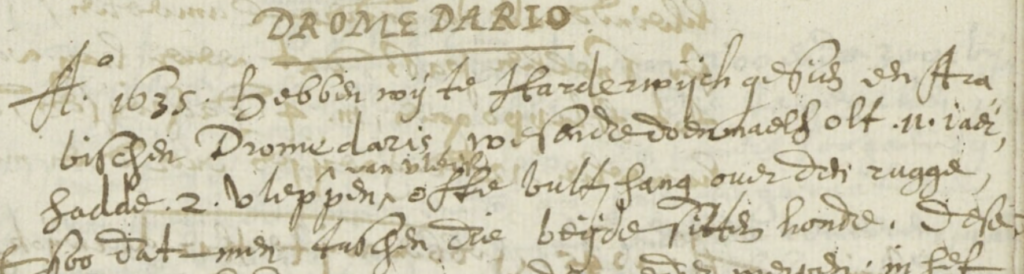

Een dromedaris met twee bulten

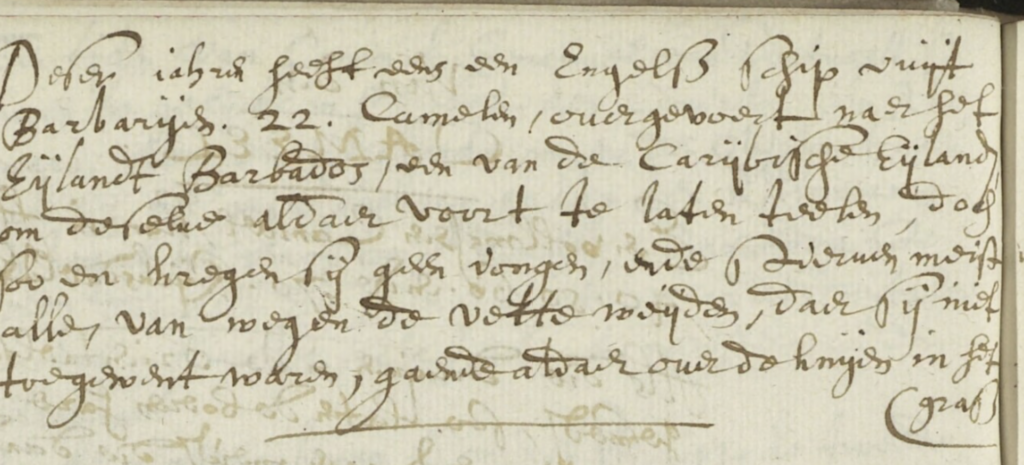

In 1633 tekende Rembrandt een kameel en noemde het dier een dromedaris. Hij was niet de enige, Ernst Brinck (1582 – 1649) zag in 1635 in zijn woonplaats Harderwijk ook een dromedaris en die had ‘2 vleppen ofte vulten’ op zijn rug ‘soo dat men tusschen die beijde sitten konde’. Mogelijk was het dezelfde kameel, in die tijd werden er allerlei dieren van kermis naar kermis en van jaarmarkt naar jaarmarkt gesleept.

Ernst Brinck schreef ook dat er 22 Noord-Afrikaanse kamelen naar het Caribische eiland Barbados werden gebracht om ze aldaar te houden en ermee te fokken. Dat laatste mislukte jammerlijk, de dieren kregen geen jongen op het eiland.

#rembrandt #ernstbrinck

Twee tweelingen (werk in uitvoering)

Op 14 september 1747 werd in het vestingstadje Ravenstein gelegen aan de Maas in de Rooms-Katholieke Sint-Luciakerk een Surinaamse tweeling gedoopt. De kinderen kregen de namen Adam Franciscus en Susanna Maria. Hoe oud zij precies waren wordt uit de doopregistratie niet duidelijk, maar wel dat ze in Suriname zijn geboren. Als vader wordt genoteerd Gerardus Hijbers van Vellip, van de moeder werd de naam niet opgeschreven, maar slechts dat zij ‘Aethipissa’ was, letterlijk ‘Ethiopische’, bedoeld werd een zwarte vrouw.

De tweeling was vijf maanden eerder samen met hun vader aan boord van het schip Jakob en Daniel van Suriname naar Europa vertrokken. Bleef de moeder achter in Suriname? Of reisde dit hele gezin naar Europa? Dat lijkt alleen al vanwege de verzorging van de kinderen logischer. Vaak werd zoiets bij vertrek in het journaal van de gouverneur genoemd, maar in dit geval helaas niet. Wat we wel weten is dat Gerardus – of liever gezegd Gerrit, zoals hij door zijn broers en zussen in een notariële akten genoemd werd – tijdens de reis aan boord van het schip is overleden. En dat de kinderen op 14 september 1747 in Ravenstein waren.

Wat zal er daarna gebeurd zijn met de tweeling en hun moeder? Bleven ze lang in Nederland, of gingen ze juist weer terug? Waren ze bij hun moeder, of kwamen ze in een weeshuis terecht? Wat zeker is, is dat Susanna op een gegeven moment weer naar Suriname is gereisd. Op 17 mei 1760 vertrekt zij namelijk (opnieuw) vanuit Paramaribo naar Amsterdam, door de gouverneur wordt zij ‘mulattin’ genoemd in het journaal.

Een tweede tweeling

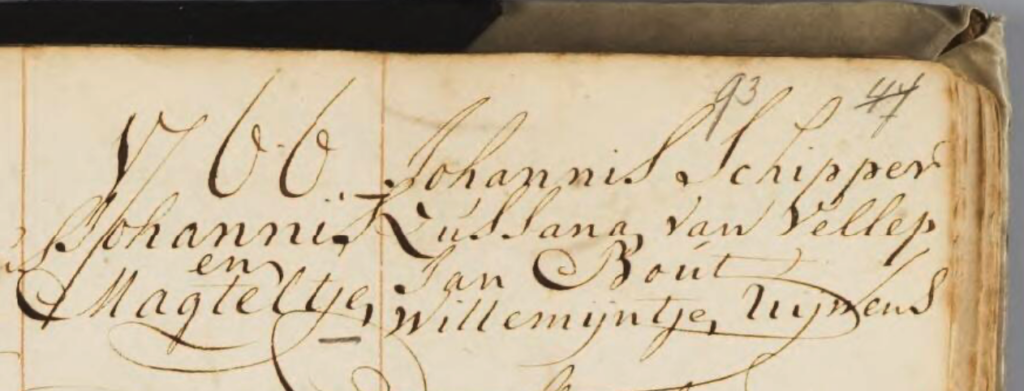

In 1766 blijkt Susanna van Vellep als getrouwde vrouw in Amsterdam te wonen met een zekere Jan Schipper. Wanneer en waar Suzanna en Jan trouwde weet ik nog niet. Zij komen niet voor in de Amsterdamse ondertrouwregisters, en die zijn compleet dus de bruiloft moet buiten Amsterdam (in Suriname?) zijn geweest. Op 16 jul 1766 hadden zij wel iets te vieren in die stad, dan wordt in de Noorderkerk in de Jordaan een tweeling gedoopt door dominee Johannes Calkoen, vader Johannis Schipper, moeder ‘Zussana van Vellep’. Het krijgen van twee-eiige tweelingen is vaak genetisch, zo blijkt ook nu weer. En net als haar moeder, van wie we nog altijd de naam niet weten, kreeg Suzanna een dochter (Magteltje) en een zoon (Johannes). Was Machteltje misschien de naam van Suzanna’s moeder?

Twee jaar later op 14 september 1768 , op de dag af 21 jaar na de doop van Adam en Suzanna, wordt er opnieuw een kind van Suzanna van Vellep en Jan Schippers in de Noorderkerk gedoopt. Geen tweeling, maar een zoon die de naam Adam krijgt, natuurlijk vernoemd naar haar tweelingbroer. Die nu ook in Amsterdam aanwezig blijkt te zijn en die natuurlijk doopgetuige van zijn neefje.

In 1785 is Susanna doopgetuige van een kind dat Susanna Catrina genoemd wordt, docher van Jan Langendijk en Sara Alida Boomhoff, vernoemd naar Susanna van Velp dus. En in 1786 zijn Adam en Susanna samen getuige bij het in Amsterdam geboren kind Jan, zoon van Sijbrant Kraaneveld en Anna Angel.

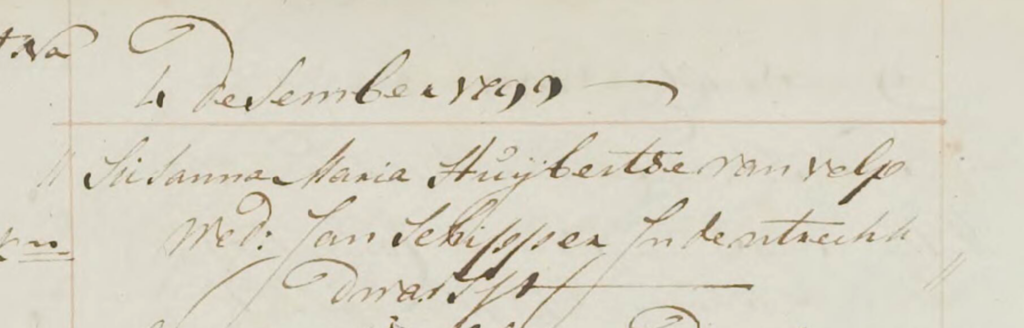

Wat Suzanna en Adam precies deden weet ik nog niet. Van Suzanna hebben we nog een belangrijk spoor waaruit blijkt dat ze nog dertig jaar geleefd heeft, waarschijnlijk al die tijd in Amsterdam. Op 4 december 1799 wordt namelijk op het Amsterdamse Leidse kerkhof Susanna Maria Huijbertse van Velp, weduwe van Jan Schipper, begraven. Op het moment van overlijden woonde Suzanna in de Utrechtse Dwarsstraat.Wat Suzanna en Adam precies deden weet ik nog niet. Van Suzanna hebben we nog een belangrijk spoor waaruit blijkt dat ze nog dertig jaar geleefd heeft, waarschijnlijk al die tijd in Amsterdam. Op 4 december 1799 wordt namelijk op het Amsterdamse Leidse kerkhof Susanna Maria Huijbertse van Velp, weduwe van Jan Schipper, begraven. Op het moment van overlijden woonde Suzanna in de Utrechtse Dwarsstraat.

Van Adam en de overige familieleden ontbreekt verder nog ieder spoor. Maar daar komt vast snel verandering in.

Mark Ponte

Alle Amsterdamse Apen

Iedere maandagmiddag duikt NH Radio met wisselende historici de geschiedenis in, vandaag was het mijn beurt. Ik sprak over apen in de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw.

Anti-christelijke taal van een Turkse koopman op de Nieuwmarkt

AMSTERDAMSE AKTEN • 7 augustus 2023 • Door Mark Ponte

De Turkse koopman Mustaffa had schulden, liet zich kwalijk uit over christelijke zaken en bedreigde mensen. Stadgenoten rapporteren erover bij de notaris.

De Amsterdamse Notariele Akten uit de 17de en 18de eeuw geven unieke inkijkjes in het internationale karakter van de stad Amsterdam. In de omgeving van de Nieuwmarkt bevond zich een groep kooplieden, bestaande uit Grieken, Armeniërs, Turken en Italianen. Zij werden aangetrokken door de mogelijkheden op de Amsterdamse koopmansbeurs en verbleven voor korte of langere tijd in de handelsstad. Ze hadden een vaste stek op de beurs en ze woonden of logeerden onder meer op de Sint Antoniebreestraat ‘in de Persiaen’, in logementen in de Bethaniënstraat of op de Boomsloten, waar in de 18de eeuw de nog altijd bestaande Armeense kerk gebouwd werd.

De meeste van deze migranten kwamen uit de Levant, Turkije, Armenië of Iran, maar ze hadden nogal wisselende ‘identiteiten’ – de landsgrenzen van vandaag lagen vroeger anders. Zo identificeerde de uit Constantinopel afkomstige kruidenier Jean Gaston zich als ‘Armeniër’ en was de ‘Griek’ Jan Elias afkomstig uit Aleppo (zie Ons Amsterdam van februari 2023). Gaston gebruikte in zijn akten het Latijns schrift, Elias het Arabisch.

Hun handelsnetwerken strekten zich dan ook uit rond de Middellandse Zee en verder langs de Zwarte Zee en Indische Oceaan, en ze waren bovendien verbonden aan eeuwenoude routes over land. Bij de Amsterdamse notarissen kwamen zij vooral langs om handelscontracten te tekenen, maar ook om verslag te doen van conflicten die zich regelmatig binnen de gemeenschap afspeelden.

Zoals in 1656, rond de Turkse koopman Mustaffa. Die was dat jaar met handelswaar uit Venetië in Amsterdam aangekomen en hij had onderdak gevonden bij de Armeniër Gregorius Martinus op de Boomsloot. Op verzoek van de laatste vertellen Jan Elias, ‘Grieks coopman’, Juanni Jacob, Tatos Baba, Demetry Augustus en Joannes Petri op 5 december 1656 bij de notaris in aanwezigheid van Sirkis Bogos, ‘tolck van de Asiatische taelen’, dat zij erbij waren toen Gregorius enkele maanden eerder ‘met Mustaffa Turck afreeckende van eenige penningen, die de requirant met Mustaffa tot zijne noodige onderhout & montcosten hijer ter landen t’sedert zijne comste van Venetien verstreckt hadde’.

Den swaren Orancan op Sint Christoffel

Net als de huidige bewoners van het Caraïbisch gebied, konden zeventiende-eeuwse koopvaarders en kolonisten in de maanden juni tot en met november te maken krijgen met tropische cyclonen. Op 27 oktober 1639 verklaarde schipper Michiel Sijmonsz van Uitgeest bij Notaris Henrick Schaef over een zware storm die een jaar eerder ver het eiland Sint Christoffel raasde, waarbij verschillende schepen verloren gingen en gouverneur Pieter Minuit van Nieuw-Zweden om het leven kwam.

Nieuw-Zweden

Nadat hij eerder van 1626 tot 1631 gouverneur was geweest van Nieuw-Nederland, trad Peter Minuit in 1637 in dienst van de Zweedse kroon met de opdracht een kolonie te stichten in Noord-Amerika. In het voorjaar van 1638 streek hij met een groep Zweedse kolonisten neer in het gebied rond de Delaware Rivier, aan de zuidgrens van Nieuw-Nederland. Daar werd de kolonie Nieuw-Zweden gesticht en direct een aanvang gemaakt met de bouw van Fort Christina. In juni 1638 was Minuit alweer onderweg met het schip de Calmar Sleutel (in het Zweeds de Kalmar Nickel) om in Zweden een tweede groep kolonisten op te halen. Bij het eiland St. Christoffel, het huidige St. Kitts, werd een tussenstop gemaakt om te handelen in tabak.

Kaart St. Christoffel in circa. 1760 ( Bron)

Swaren Orancan

Er lagen diverse schepen op de rede bij Sandt Punct (Sandy Point), de tabakshaven van St Christoffel. Terwijl er door het lagere personeel van de Calmar Sleutel druk gehandeld werd, waren schipper Jan van Water en commandeur Minuit op 28 juni 1638 van boord gegaan om op uitnodiging van een collega schipper te dineren op het Rotterdamse schip ‘Het vliegende hert’.

Aan boord van de Calmar Sleutel waren zes bemanningsleden van het schip de Santa Clara om een partij tabak te ruilen tegen een aantal papegaaien. Terwijl onderstuurman Jacob Evertsz nog bezig was met het wegen van de tabak, werd St. Christoffel één uur voor zonsondergang overvallen door ‘den swaren Orancan‘. De zware tropisch storm raasde over de rede van de Sandt Punt, verschillende schepen raken op drift en vergaan in de Caribische Zee. Zowel Het Vliegende Hert als de Santa Clara verdwijnen uit het zicht. Van commandeur Peter Minuit en schipper Jan de Water is nooit meer iets vernomen.

De Kalmar Nyckel is weliswaar een flink stuk afgedreven van het eiland, maar wonder boven wonder nauwelijks beschadigd. Twee dagen later lukt het de bemanning om al laverend de Sandt Punct te bereiken. Vijf van de zes bemanningsleden van de Santa Clara die tijdens de orkaan aan boord waren, worden in dienst genomen, en niet lang daarna vertrekt het schip richting Europa. Twee jaar later, in 1640, bracht het een tweede groep kolonisten in Nieuw-Zweden. In 1652 werd het schip tijdens de Eerste Engelse Zeeoorlog voor de kust van Schotland tot zinken gebracht.

Schilderij Kalmar Nyckel, door Jacob Hägg, 1922

Etymologie van orkaan

Een bijzondere akte, niet alleen vanwege de heftige gebeurtenis die wordt beschreven en de vele achterliggende verhalen die een rol spelen, maar ook vanwege het gebruik van het woord ‘Orancan’. Een woord dat waarschijnlijk afkomstig is uit het Taino, een Arawakse taal uit het Caribisch gebied. Nergens werd het woord storm gebruikt, in plaats daarvan sprak Michiel Sijmonsz over ‘Den Swaren Orancan’, als ware het een reusachtig angstaanjagend beest dat schepen verschalkte. Het is dan ook dit Caribische woord Orancan, waar ons woord orkaan en ook het Engelse Huricane, op gebaseerd is. Niet alleen de tabak en suiker werden uit het Caribisch gebied naar Europa gehaald, soms ook, zo blijkt uit dit verhaal, de taal omdat de eigen woorden te kort schoten om een gebeurtenis te beschrijven.

- In de jaren negentig van de twintigste eeuw is er een replica gemaakt van de Calmar Nyckel, zie http://www.kalmarnyckel.org/.

- Wikipedia: Nieuw-Zweden, Peter Minuit, St. Christoffel

- Etymologie van het woord orkaan

- Shipwreck rates reveal Caribbean tropical cyclone response to past radiative forcing, in ‘Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences’ over het gebruik van historische data bij onderzoek naar tropische cyclonen.

In 2017 gepubliceerd op www.alleamsterdamseakten.nl

Schilderij: Claes Claesz. Wou, Museum Fine Arts, Budapest

Famiri

Als die tentoonstelling er niet was geweest hadden zij elkaar niet leren kennen en waren wij er niet geweest”, aldus Malaika Frijmersum. In de tentoonstelling Famiri Familie de bijzondere Amsterdams-Surinaamse familiegeschiedenis van de familie Frijmersum-Mazer.

De tentoonstelling is te zien in Stadsarchief Amsterdam, Nationaal Archief Suriname en in CEC Zuidoost Vorige week zondag was ik met Goziëm Frijmersumte gast bij OVT VPRO.

Lees meer over Famiri Familie. Surinaams-Amsterdamse verhalen vanaf 1611

Foto 1, 28 juni 2023 in het Stadsarchief Amsterdam, door Maarten Nauw

Foto 2, 29 juni 1934 Dr. H.D. Benjaminsschool, Paramaribo, Fotograaf onbekend

Slavernij in Nederland?

Dit is mijn korte bijdrage aan de publicatie Staat en Slavernij. Het koloniale slavernijverleden en zijn doorwerkingen. Gepubliceerd bij Athenaeum–Polak & Van Gennep | Amsterdam 2023 en tussen de kamerstukken.

In juli 1683 ging in de Stadsschouwburg van Amsterdam het toneelstuk ‘De Belachelijke Jonker’ van Pieter Bernagie (1656-1699) in première. Het was een hit en het werd in de decennia daarna tientallen keren opgevoerd. Een van de hoofdpersonen is Joris, die na een carrière van ruim dertig jaar in Azië terugkeert in Amsterdam. In de op een na laatste scène blijkt dat de VOC-veteraan naast goederen en mooie Aziatische kleren ook twee Zwarte bedienden heeft meegebracht, niet voor zichzelf maar voor een belangrijk heer. ‘Wel broer neem jij twee zwarten meede?’ vraagt zijn zus aan hem. ‘Ja, ’t is om aan een magtig Heer Te geeven, zy verstaan ’t geweer, Zy konnen danssen,’ antwoordt hij.1 Hoewel het hier om fictie gaat, laat het stuk zien dat de praktijk van het meenemen en weggeven van bedienden een normaal verschijnsel was in de toenmalige Republiek. Zo hebben er aan het hof van de Oranjes in Den Haag diverse mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst gewerkt, van wie een aantal als kind ‘cadeau’ werd gedaan aan het Hof.2 Ook op vele andere plekken in de Republiek, tot ver buiten Holland, hebben Zwarte bedienden gewerkt, zoals in Gelderland, Groningen en Friesland.

De laatste jaren zijn er verschillende onderzoeken verschenen naar slavernij en naar mensen uit de gekoloniseerde gebieden die terechtkwamen in de Republiek. Men richt zich daarbij tot nu toe vooral op de grote steden. De resultaten maken duidelijk dat terwijl de Nederlanders de wereld over trokken, de wereld ook naar Nederland kwam. Weliswaar vond de kolonisatie, het daad- werkelijk tot slaaf maken van mensen en hen in slavernij tewerkstellen door Nederlanders overzee plaats in Afrika, Azië en Amerika, maar dat alles werd vanuit de Republiek georganiseerd. En vanaf het begin kwamen daardoor niet alleen koloniale producten maar ook mensen aan in de Republiek. Al tijdens de zogenaamde ‘Eerste scheepvaart’ naar Azië maakte de bemanning mensen tot slaaf en nam ze mee terug.3

Vroeg in de zeventiende eeuw vormde zich in Amsterdam al een kleine vrije Zwarte gemeenschap. De meeste vrouwen in deze gemeenschap kwamen mee met kooplieden uit Spanje, Portugal en Nederlands-Brazilië en belandden zo in Amsterdam; de mannen waren vooral Zwarte zeelieden en soldaten. Met de komst van bedienden die werkten in slavernij werd de kwestie in Amsterdam

— 218 —

weer actueel. Dat is terug te zien in de wetgeving uit die tijd. In de keurboeken, oftewel stadsrechtsboeken, van Amsterdam is vanaf 1644 een bepaling over slavernij opgenomen. De letterlijke kopie van een Antwerpse bepaling die teruggaat tot in de zestiende eeuw laat zien dat slavernij in de stad formeel verboden was: ‘Binnen der Stadt van Amstelredamme ende hare vrijheydt, zijn alle menschen vrij, ende gene Slaven.’ Het was echter aan de slaafgemaakte om zijn of haar vrijheid op te eisen. Net als in Antwerpen (zie hoofdstuk 24 van Jeroen Puttevils) kon daardoor in de steden van de Republiek de praktijk van slavernij blijven bestaan. Recent onderzoek laat zien dat verschillende slaafgemaakte vrouwen uit Nederlands-Brazilië in Amsterdam in de jaren 1650 actief hun vrijheid opeisten.4

Net als uit ‘de West’ werden ook uit de koloniale gebieden in Azië regelmatig slaafgemaakte Aziaten meegenomen naar de Republiek. De VOC probeerde dat tegen te gaan. In 1636 werd het verboden, en dat verbod werd in de jaren daarna regelmatig herhaald. Een uitzondering werd gemaakt voor de slaafgemaakten van de hoogste beambten en voor de slaafgemaakte vrouwen die zuigelingen verzorgden. De Heren Zeventien bepaalden bovendien dat de eigenaar van tevoren een borg moest storten waarmee de terugreis kon worden betaald. De mensen die het betrof waren vanaf het moment dat zij voet op Republikeinse bodem zetten formeel vrij. Maar dat wil niet zeggen dat zij direct hun ‘meesters’ konden verlaten. Ze bleven meestal gewoon in dienst en verkeerden zo lange tijd in een afhankelijke positie.

In de loop van de achttiende eeuw reisden steeds vaker kooplieden en plantage- eigenaren uit de Caribische plantagekoloniën, Suriname, Berbice en Demerara, naar de Republiek, voor zaken of om zich daar permanent te vestigen. Zij namen vaak slaafgemaakte bedienden mee. In de loop van de achttiende eeuw nam de komst van slaafgemaakten dan ook flink toe. De Surinaamse gouverneurs- journalen tonen het komen en gaan van plantage-eigenaren en anderen met hun slaafgemaakte bedienden.

Tot diep in de achttiende eeuw veranderde er meestal weinig aan de status van slaafgemaakten als ze in de Republiek waren of weer waren teruggekeerd. Door de onduidelijkheid in stedelijke wetgeving en met betrekking tot handhaving kon slavernij in de praktijk dus in de Republiek voortduren. Twee Afro-Surinaamse vrouwen, Marijtje Criool en haar dochter Jacoba Leilad, brachten daar in 1771 verandering in door bij de Staten-Generaal persoonlijk om vrijbrieven te vragen,

— 219 —

zodat ze als vrije mensen naar Suriname konden terugkeren. De Staten-Generaal besloten, gebaseerd op de oude wetgeving uit de zeventiende eeuw, dat de Republiek geen slavernij kende en dat vrijbrieven dus niet nodig waren. Die beslissing leidde tot onrust onder de planters in Suriname en Amsterdamse investeerders, die bang waren om zo hun ‘geïnvesteerde kapitaal’ kwijt te raken. Om hun tegemoet te komen, pasten de Staten-Generaal de regelgeving aan, en in 1776 werd bepaald dat ‘slaven’ die in de Republiek aankwamen niet automatisch vrij waren, maar pas na een half jaar, met de mogelijkheid tot verlenging van nog een half jaar. Als de persoon in kwestie na dat jaar nog niet was teruggestuurd naar Suriname was hij of zij automatisch vrij, ook bij terugkeer naar de kolonie. Maar zelfs daarna werd dit nog af en toe met succes betwist door slaveneigenaren. Die situatie bleef bestaan tot de slavernij daadwerkelijk werd afgeschaft, in 1860 in Nederlands-Indië en in 1863 in het Caribisch gebied.

Noten

- Pieter Bernagie, De belachelijke jonker en Studente-leven (1882), oorspronkelijkuitgegeven in 1683.

- Esther Schreuder, Cupido en Sideron, Twee Moren aan het hof van Oranje (Amsterdam2017).

- Leendert van der Valk, ‘Jongens van goeden begrijpe,’ De Groene Amsterdammer, nr. 25,(22 juni 2022).

- Mark Ponte, ‘Zwarte vrouwen in het middenvan de zeventiende eeuw,’ in: Maarten Hell (red.), Amstelodamum. Alle Amsterdamse Akten. Ruzie, rouw en roddels bij de notaris, 1578-1915 (Amsterdam 2022) 130143.

Mark Ponte ‘Slavernij in Nederland?’, in: Rose Mary Allen, Esther Captain, Matthias van Rossum, Urwin Vyent (ed.), Staat en Slavernij. Het koloniale slavernijverleden en zijn doorwerkingen (Athenaeum–Polak & Van Gennep | Amsterdam 2023) 218-220.