Published in: ‘Black in Rembrandt’s Time’, 2020.

In the archives, we often stumble across fragments of human lives: declarations, authorizations, or contracts that demonstrate the existence of a person otherwise absent from the historical record. Many thousands of Amsterdam men took to the sea in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), Dutch West India Company (WIC), or merchant marine. This undoubtedly also applies to black Amsterdammers. Some of them probably never visited a public notary or served as a godparent at a baptism. For a few of them, some traces of their lives have been preserved. A case in point is the married couple Lijsbeth Pieters of Angola and Pieter Claesz Bruijn of Brasil.

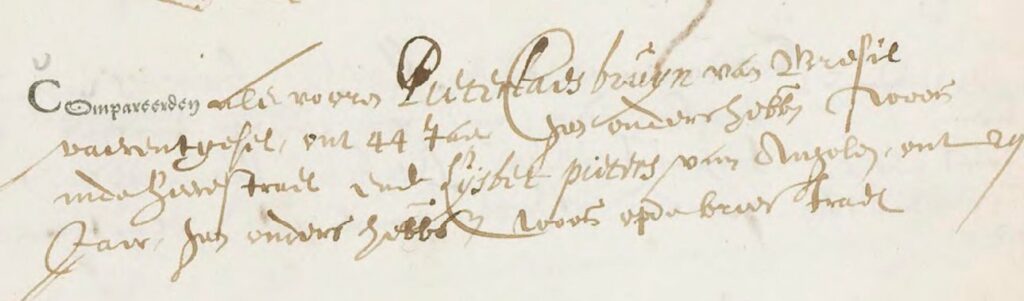

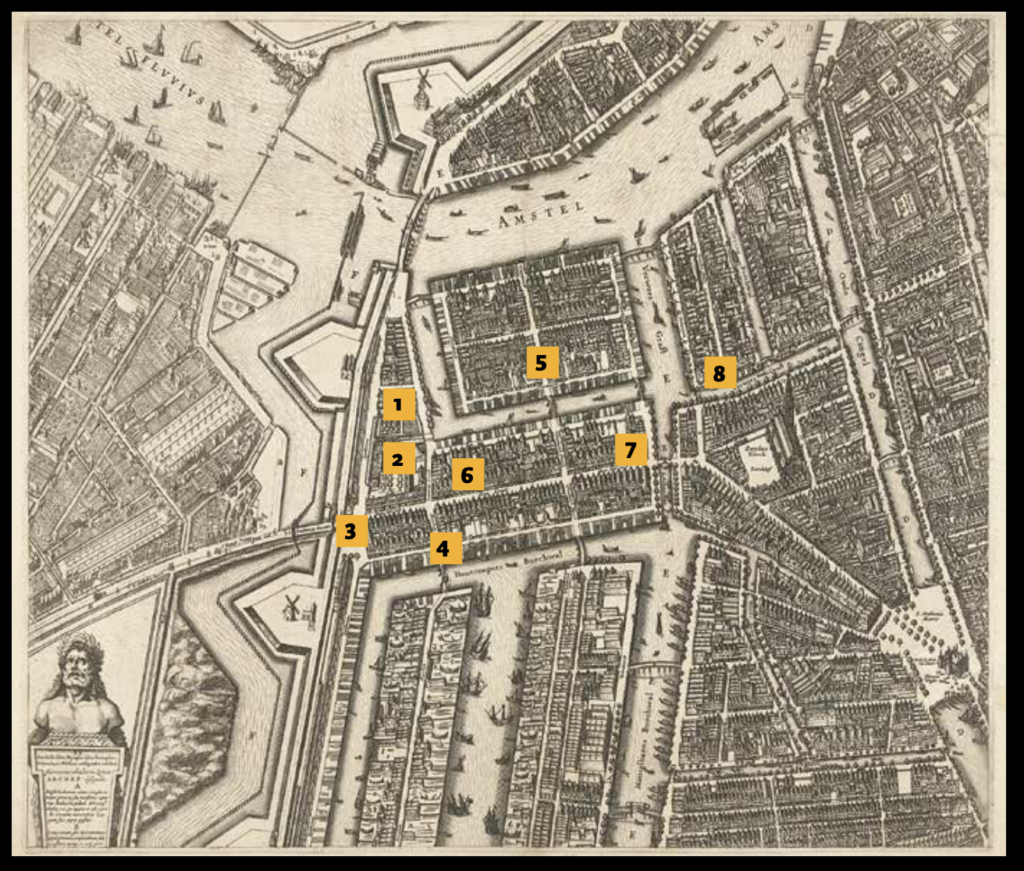

Shortly before four o’clock on 23 March 1640, Pieter Claesz Swart of Brasil entered the office of Henrick Schaeff, behind WIC headquarters on Haarlemmerdijk, accompanied by Willem de Keijser of Middelburg. Schaeff was both a notary and a clerk for the WIC, and the boundary between his two roles was often blurred. Thousands of sailors on the verge of departing for the Atlantic region – territories ranging from West Africa and Brazil to New Amsterdam and North America – visited him for various purposes, such as signing letters of debt to the many local innkeepers, thus pledging away much of their pay. Both Pieter and Willem worked for the WIC, and they had accumulated debts of 50 and 100 guilders respectively to Jan Pietersz Santdrager and his wife Anna Jansz in Amsterdam.

Pieter Claesz Swart was a man of colour. He was a bosschieter – an able seaman – from Brazil, and in 1640 he was about to embark on a new voyage on the WIC yacht Goerree. One of the two notarial deeds that Pieter Claesz signed that day describes him as speaking the Dutch language proficiently. Four years later, Pieter Claesz was back in Amsterdam, where he again accumulated a debt to the keeper of a hostelry in the Jordaan district, this time amounting to no less than 124 guilders, easily a year’s salary for a seaman. This time, interestingly, he is referred to as Peter Claesz Bruijn van Brazilië. (Swart means ‘Black’ and Bruijn means ‘Brown’.) This is the name under which he was later known. In January 1644, he went to sea again, this time on the WIC vessel Mauritius.

At that time, Pieter Claesz was not yet in touch with the small black community around Jodenbreestraat. He accumulated his debts in inns for white people, and the witnesses to his notarial deeds were white. By the late 1640s and 1650s, this situation had changed. In November 1649, when Pieter Claesz was 44 years old, he registered to marry to Lijsbeth Pieters of Angola, whom the notarial deed listed as living in Jodenbreestraat. He probably moved in with her. It is not clear whether he returned to sea after that or remained in Amsterdam. What we do know is that he was in Amsterdam in 1659. In August and October he was a witness to the baptisms of black children in the Catholic house church in the Huis Moyses in Jodenbreestraat. The first of these children, Pieter – undoubtedly named after Pieter Claesz – was the son of Alexander van Angola and Lijsbeth Dames. The second child – Catharina – was the daughter of Louis and Esperanza Alphonse. That same day, Nicolaus, the son of Emanuel and Branca Alphonse, was also baptized. The witness was Lijsbeth Pieters. She had also acted as a witness a few years earlier, in 1657, at the baptism of that couple’s first child Lucretia, as well as for Lucia, the daughter of Bastiaan and Maria Ferdinandes. These are all names of people from the small black community in and around Jodenbreestraat, of which Pieter and Lijsbeth had become important members.

How to cite: Mark Ponte, ‘Pieter Claesz Bruijn and Lijsbeth Pieters’, in: Elmer Kolfin and Epco Runia ed., Black in Rembrandt’s Time, W Books / The Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam 2020, 60-61.

Beste Mark, ik vroeg me af of je bij je onderzoek ook iets hebt ontdekt over de verhouding tussen de Zwarte gemeenschap en de Portugees-Joodse buurtbewoners. Zij hadden immers banden met de trans~Atlantische (slaven)handel en o. a. in Suriname de Jodensavanne gesticht.

Zeker, daar heb ik ook veel over geschreven, ook hier te vinden:

https://voetnoot.org/2021/01/25/mostly-slaves-and-moors/

https://voetnoot.org/2020/12/24/tussen-slavernij-en-vrijheid-in-amsterdam/

https://voetnoot.org/2022/06/15/een-slaafgemaakte-familie-in-amsterdam/

https://onsamsterdam.nl/juliana-eist-haar-vrijheid-op

Ponte, M. (2019). ’Al de swarten die hier ter stede comen’ Een Afro-Atlantische gemeenschap in zeventiende-eeuws Amsterdam. TSEG – The Low Countries Journal of Social and Economic History, 15(4), 33–62. https://doi.org/10.18352/tseg.995

Meest recent is:

Mark Ponte, ‘Zwarte vrouwen in het midden van de zeventiende eeuw’, in: Maarten Hell ed., Amstelodomum. Alle Amsterdamse Akten. Ruzie, rouw en roddels bij de notaris, 1578-1915