Dit is mijn korte bijdrage aan de publicatie Staat en Slavernij. Het koloniale slavernijverleden en zijn doorwerkingen. Gepubliceerd bij Athenaeum–Polak & Van Gennep | Amsterdam 2023 en tussen de kamerstukken.

In juli 1683 ging in de Stadsschouwburg van Amsterdam het toneelstuk ‘De Belachelijke Jonker’ van Pieter Bernagie (1656-1699) in première. Het was een hit en het werd in de decennia daarna tientallen keren opgevoerd. Een van de hoofdpersonen is Joris, die na een carrière van ruim dertig jaar in Azië terugkeert in Amsterdam. In de op een na laatste scène blijkt dat de VOC-veteraan naast goederen en mooie Aziatische kleren ook twee Zwarte bedienden heeft meegebracht, niet voor zichzelf maar voor een belangrijk heer. ‘Wel broer neem jij twee zwarten meede?’ vraagt zijn zus aan hem. ‘Ja, ’t is om aan een magtig Heer Te geeven, zy verstaan ’t geweer, Zy konnen danssen,’ antwoordt hij.1 Hoewel het hier om fictie gaat, laat het stuk zien dat de praktijk van het meenemen en weggeven van bedienden een normaal verschijnsel was in de toenmalige Republiek. Zo hebben er aan het hof van de Oranjes in Den Haag diverse mensen van Afrikaanse herkomst gewerkt, van wie een aantal als kind ‘cadeau’ werd gedaan aan het Hof.2 Ook op vele andere plekken in de Republiek, tot ver buiten Holland, hebben Zwarte bedienden gewerkt, zoals in Gelderland, Groningen en Friesland.

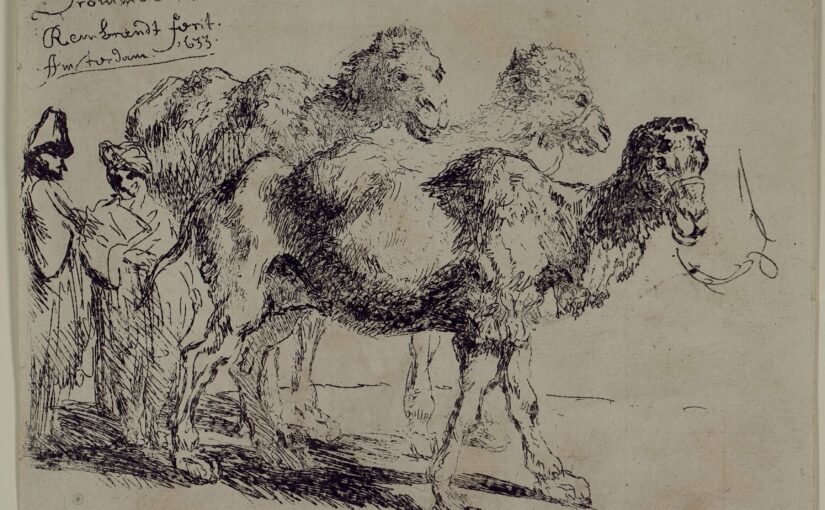

De laatste jaren zijn er verschillende onderzoeken verschenen naar slavernij en naar mensen uit de gekoloniseerde gebieden die terechtkwamen in de Republiek. Men richt zich daarbij tot nu toe vooral op de grote steden. De resultaten maken duidelijk dat terwijl de Nederlanders de wereld over trokken, de wereld ook naar Nederland kwam. Weliswaar vond de kolonisatie, het daad- werkelijk tot slaaf maken van mensen en hen in slavernij tewerkstellen door Nederlanders overzee plaats in Afrika, Azië en Amerika, maar dat alles werd vanuit de Republiek georganiseerd. En vanaf het begin kwamen daardoor niet alleen koloniale producten maar ook mensen aan in de Republiek. Al tijdens de zogenaamde ‘Eerste scheepvaart’ naar Azië maakte de bemanning mensen tot slaaf en nam ze mee terug.3

Vroeg in de zeventiende eeuw vormde zich in Amsterdam al een kleine vrije Zwarte gemeenschap. De meeste vrouwen in deze gemeenschap kwamen mee met kooplieden uit Spanje, Portugal en Nederlands-Brazilië en belandden zo in Amsterdam; de mannen waren vooral Zwarte zeelieden en soldaten. Met de komst van bedienden die werkten in slavernij werd de kwestie in Amsterdam

— 218 —

weer actueel. Dat is terug te zien in de wetgeving uit die tijd. In de keurboeken, oftewel stadsrechtsboeken, van Amsterdam is vanaf 1644 een bepaling over slavernij opgenomen. De letterlijke kopie van een Antwerpse bepaling die teruggaat tot in de zestiende eeuw laat zien dat slavernij in de stad formeel verboden was: ‘Binnen der Stadt van Amstelredamme ende hare vrijheydt, zijn alle menschen vrij, ende gene Slaven.’ Het was echter aan de slaafgemaakte om zijn of haar vrijheid op te eisen. Net als in Antwerpen (zie hoofdstuk 24 van Jeroen Puttevils) kon daardoor in de steden van de Republiek de praktijk van slavernij blijven bestaan. Recent onderzoek laat zien dat verschillende slaafgemaakte vrouwen uit Nederlands-Brazilië in Amsterdam in de jaren 1650 actief hun vrijheid opeisten.4

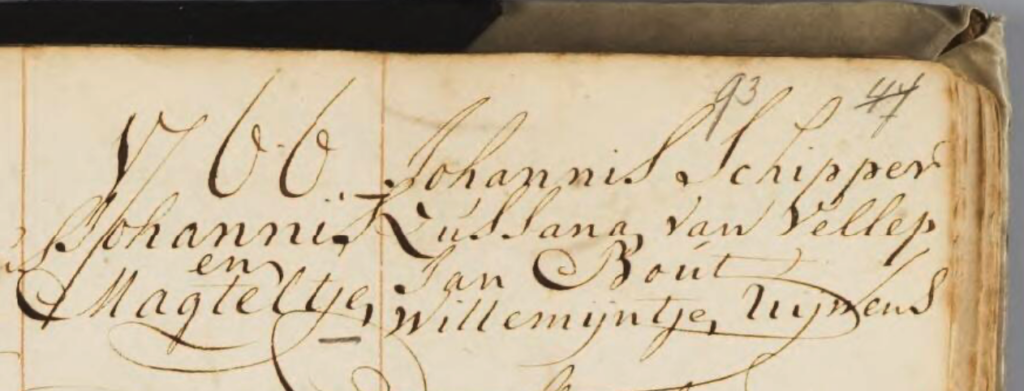

Net als uit ‘de West’ werden ook uit de koloniale gebieden in Azië regelmatig slaafgemaakte Aziaten meegenomen naar de Republiek. De VOC probeerde dat tegen te gaan. In 1636 werd het verboden, en dat verbod werd in de jaren daarna regelmatig herhaald. Een uitzondering werd gemaakt voor de slaafgemaakten van de hoogste beambten en voor de slaafgemaakte vrouwen die zuigelingen verzorgden. De Heren Zeventien bepaalden bovendien dat de eigenaar van tevoren een borg moest storten waarmee de terugreis kon worden betaald. De mensen die het betrof waren vanaf het moment dat zij voet op Republikeinse bodem zetten formeel vrij. Maar dat wil niet zeggen dat zij direct hun ‘meesters’ konden verlaten. Ze bleven meestal gewoon in dienst en verkeerden zo lange tijd in een afhankelijke positie.

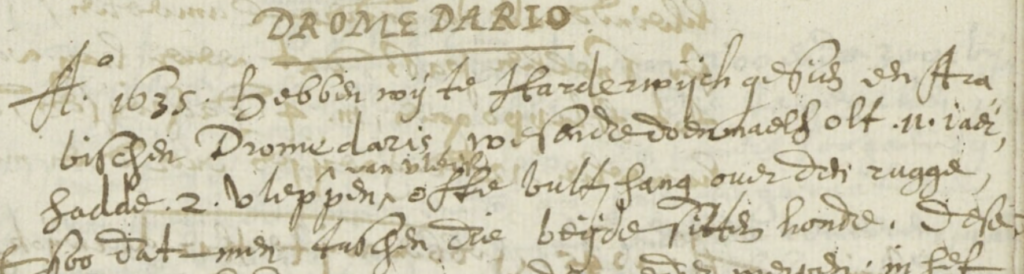

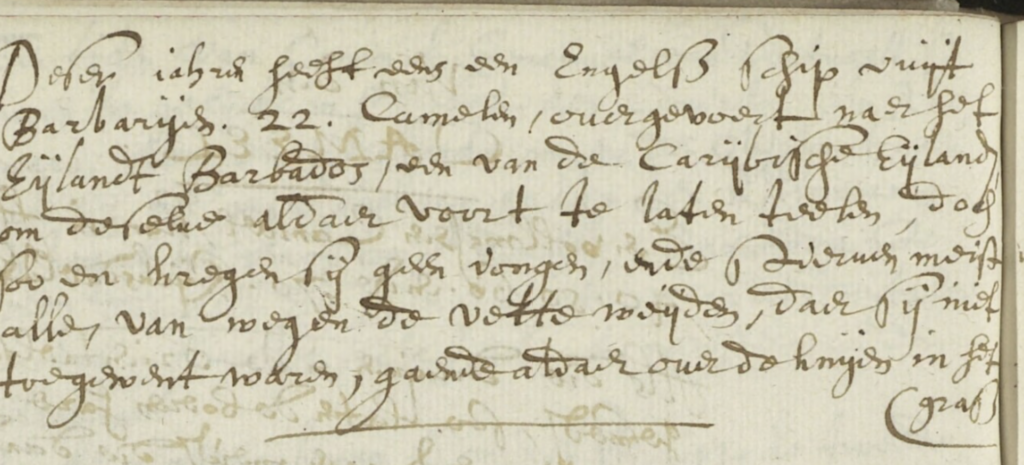

In de loop van de achttiende eeuw reisden steeds vaker kooplieden en plantage- eigenaren uit de Caribische plantagekoloniën, Suriname, Berbice en Demerara, naar de Republiek, voor zaken of om zich daar permanent te vestigen. Zij namen vaak slaafgemaakte bedienden mee. In de loop van de achttiende eeuw nam de komst van slaafgemaakten dan ook flink toe. De Surinaamse gouverneurs- journalen tonen het komen en gaan van plantage-eigenaren en anderen met hun slaafgemaakte bedienden.

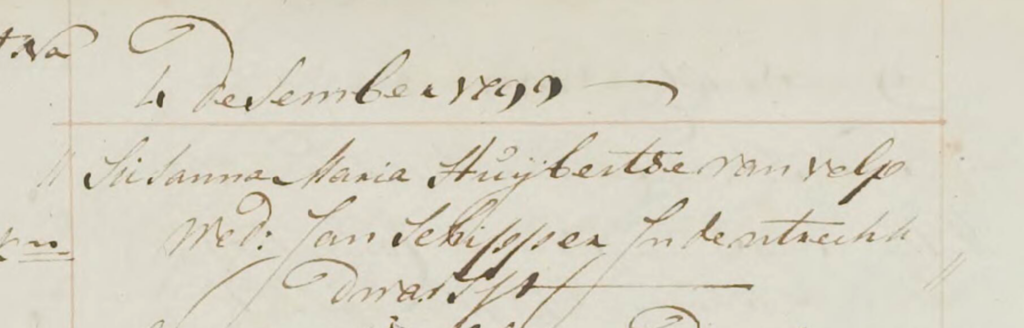

Tot diep in de achttiende eeuw veranderde er meestal weinig aan de status van slaafgemaakten als ze in de Republiek waren of weer waren teruggekeerd. Door de onduidelijkheid in stedelijke wetgeving en met betrekking tot handhaving kon slavernij in de praktijk dus in de Republiek voortduren. Twee Afro-Surinaamse vrouwen, Marijtje Criool en haar dochter Jacoba Leilad, brachten daar in 1771 verandering in door bij de Staten-Generaal persoonlijk om vrijbrieven te vragen,

— 219 —

zodat ze als vrije mensen naar Suriname konden terugkeren. De Staten-Generaal besloten, gebaseerd op de oude wetgeving uit de zeventiende eeuw, dat de Republiek geen slavernij kende en dat vrijbrieven dus niet nodig waren. Die beslissing leidde tot onrust onder de planters in Suriname en Amsterdamse investeerders, die bang waren om zo hun ‘geïnvesteerde kapitaal’ kwijt te raken. Om hun tegemoet te komen, pasten de Staten-Generaal de regelgeving aan, en in 1776 werd bepaald dat ‘slaven’ die in de Republiek aankwamen niet automatisch vrij waren, maar pas na een half jaar, met de mogelijkheid tot verlenging van nog een half jaar. Als de persoon in kwestie na dat jaar nog niet was teruggestuurd naar Suriname was hij of zij automatisch vrij, ook bij terugkeer naar de kolonie. Maar zelfs daarna werd dit nog af en toe met succes betwist door slaveneigenaren. Die situatie bleef bestaan tot de slavernij daadwerkelijk werd afgeschaft, in 1860 in Nederlands-Indië en in 1863 in het Caribisch gebied.

Noten

- Pieter Bernagie, De belachelijke jonker en Studente-leven (1882), oorspronkelijkuitgegeven in 1683.

- Esther Schreuder, Cupido en Sideron, Twee Moren aan het hof van Oranje (Amsterdam2017).

- Leendert van der Valk, ‘Jongens van goeden begrijpe,’ De Groene Amsterdammer, nr. 25,(22 juni 2022).

- Mark Ponte, ‘Zwarte vrouwen in het middenvan de zeventiende eeuw,’ in: Maarten Hell (red.), Amstelodamum. Alle Amsterdamse Akten. Ruzie, rouw en roddels bij de notaris, 1578-1915 (Amsterdam 2022) 130143.

Mark Ponte ‘Slavernij in Nederland?’, in: Rose Mary Allen, Esther Captain, Matthias van Rossum, Urwin Vyent (ed.), Staat en Slavernij. Het koloniale slavernijverleden en zijn doorwerkingen (Athenaeum–Polak & Van Gennep | Amsterdam 2023) 218-220.