Voor Nederlandse versie zie hier

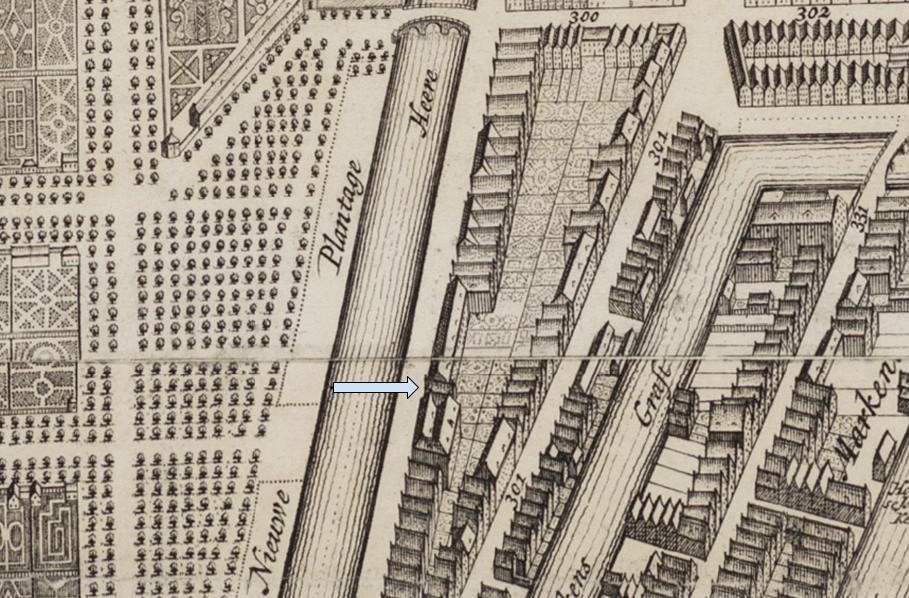

In 1783 Anthony, his wife Magdalena and their son Emanuel were taken from Curaçao to Amsterdam. There they ended up in a house on Nieuwe Herengracht, currently number 105. Anthony was the personal servant of the old merchant Isaac Pardo. Magdalena also worked as a servant. How old Emanuel was and whether he also had to work is not known.

Anthony and his family had lived in slavery on Curaçao, in Amsterdam their status was not so clear. Slavery was not officially permitted in that city. In the lawbooks of Amsterdam, a provision on slavery was included from 1644 onwards. This Amsterdam provision was a literal copy of an Antwerp one dating back to the 16th century. Under the heading ‘Of the state and condition of persons’, it was stipulated that: Within the city of Amstelredamme and its freedom, all people are free and there are no Slaves’. This seems to be a clear stipulation that every person in Amsterdam must be considered a free person. However, the second article states that it was up to those who were held in slavery ‘against their will’ to claim their freedom from the city council. In other words, there was no active investigation.

This legislation was also known to the enslaved people on Curaçao. Some gain their freedom by hiding aboard ships and trying to reach the Republic as stowaways. Mostly in vain. In the course of the eighteenth century, there were hundreds or even a few thousend of enslaved people from Surinam, Berbice and Curaçao, among others, who stayed in Amsterdam for a time but whose legal status remained virtually the same, after their return to the colony. That situation changed when, in 1771, two Surinamese women, after a stay in the Republic, once back in Paramaribo, successfully claimed their liberty. Because of the unrest that arose among the planters of Suriname, the States General decided to restrict freedom. No longer would a slave servant in the Republic be freed immediately, but only after a stay of six months – a period that could also be extended by another six months. If he or she still lived in the Republic after that, he or she became truly free.

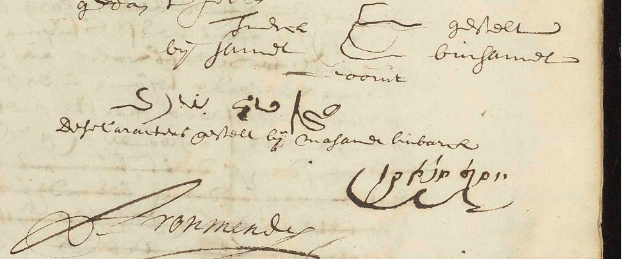

How long Anthony, Magdalena and Emanuel served at the Nieuwe Herengracht is not (yet) known. For the time being, we only know this Afro-Curaçao family from one document: the testament of the Portuguese-Jewish merchant Isaac Pardo. This document was drawn up a few months after their arrival in Amsterdam. With three witnesses, civil-law notary Johannes van de Brink travelled from his office on the Rokin to the Nieuwe Herengracht on 8 December 1783. Three instead of the usual two, because ’the testator is blind’, the notary noted at the end of the deed.

Isaac, Anthony, Magdalena and Emanuel had not been in Amsterdam that long, in September 1783 Isaac Pardo paid finta (tax) for the first time. He was taxed in the highest category and was therefore a rich man. After a long career as a merchant in Curaçao, he had decided to settle in the Republic. Perhaps he did so because of the better medical facilities. Pardo was old and by now blind, and probably largely dependent on his servants.

In his will Pardo stipulated that after his death the servant Anthony would be free and discharged from all ‘slave services’. He also instructed his children ’to provide Anthony, together with his wife Magdalena and their son Emanuel, as long as the Antony lives, with board and drink, as well as clothing and lodging in their homes’. For this they had to serve the next of kin ‘as they are at present at the service of the testator [Pardo]’. If either party, including Anthony and his family, no longer appreciated this service, Pardo’s sons had to pay Anthony 400 guilders annually. This yearly payment was not transferable to Magdalena – in case Anthony would die before. However, Magdalena and Emanuel would be allowed to return to Curaçao at the Pardo’s expense, and – very importantly – be made free.

It could be that this was the legal confirmation of an earlier agreement between Anthony, Magdalena and Isaac Pardo. As was the case earlier with the Afro-Curaçaoan Juan Francisco Ado, who arrived in Amsterdam in 1731 with Anna Levina Leendertsz, wife of the former governor of Curaçao and former alderman of Amsterdam Jan Noach du Fay. Even before leaving Curaçao, they had agreed that if the ‘slave could properly serve and guard her […] during the journey’, Ado would be granted his freedom in the Republic.

Isaac Pardo died a year and a half after drawing up his will; on 21 June 1785. He was buried at the Portuguese-Jewish cemetery in Ouderkerk aan de Amstel. A year later his ‘magnifique and distinguished’ household effects were sold. How the lives of Anthony, Magdalena and Emanuel went on, we do not know yet. Did they return to Curaçao? Or did they build their own lives in Amsterdam? Perhaps documents about them will turn up in the future in the archives of the Amsterdam notaries.