Dit artikel is verschenen in : Pepijn Brandom e.a., De slavernij in Oost en West. Het Amsterdam onderzoek (Spectrum; Amsterdam 2020) 248-256.

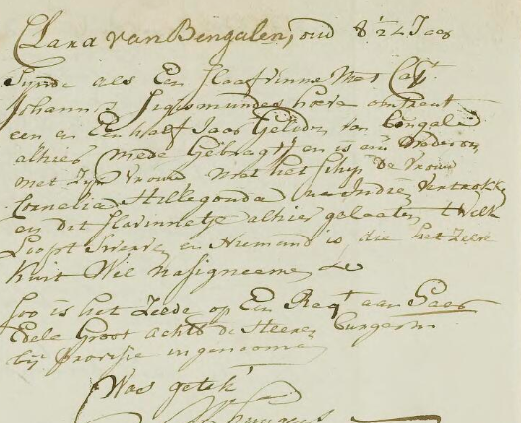

In 1656 legde de Portugese suikerhandelaar Eliau de Burgos een verklaring af bij een Amsterdamse notaris over de weggelopen zwarte vrouw genaamd Juliana, die hij in slavernij had meegenomen uit Brazilië. Burgos was van plan te vertrekken naar de plantagekolonie Barbados en wilde Juliana meenemen als bediende. Bij de notaris vertelde De Burgos dat hij haar in 1643 als meisje had gekocht voor 525 gulden, en hij haar in Brazilië makkelijk voor een vergelijkbaar bedrag had kunnen verkopen, maar dat Juliana hem gesmeekt zou hebben mee te mogen naar de Republiek.

Of dat laatste waar is kunnen we betwijfelen, maar duidelijk is dat zij eenmaal in de Republiek niet van plan was om opnieuw naar een plantagekolonie te vertrekken. Integendeel, Juliana was inmiddels door Amsterdammers op de hoogte gebracht van de wetgeving in Amsterdam die stelde dat er in de stad geen slavernij bestond, waarop zij besloot hiernaar te handelen en weg te lopen.

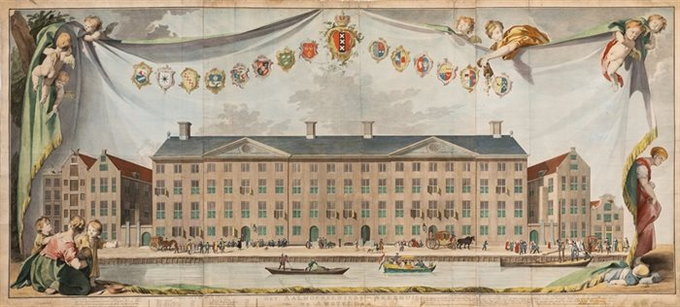

Terwijl de Amsterdammers de wereld over trokken, kwam de wereld naar Amsterdam. Vanaf het moment dat de Amsterdammers rond 1600 hun vleugels uitsloegen naar Afrika, Azië en Amerika kwamen mensen uit deze gebieden naar Amsterdam. Een deel van deze mensen had een achtergrond in slavernij, maar anderen kwamen als diplomaten, ambachtslui en zeelieden. In dit essay zal ik aan de hand van concrete voorbeelden de ontwikkeling van Atlantische en Aziatische migratie naar Amsterdam gedurende de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw schetsen. De nadruk daarbij ligt op de vraag of slavernij was toegestaan in Amsterdam.

Vrije en slaafgemaakte zwarte Amsterdammers in de zeventiende eeuw

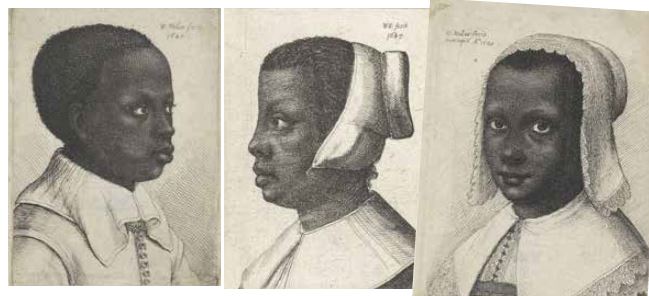

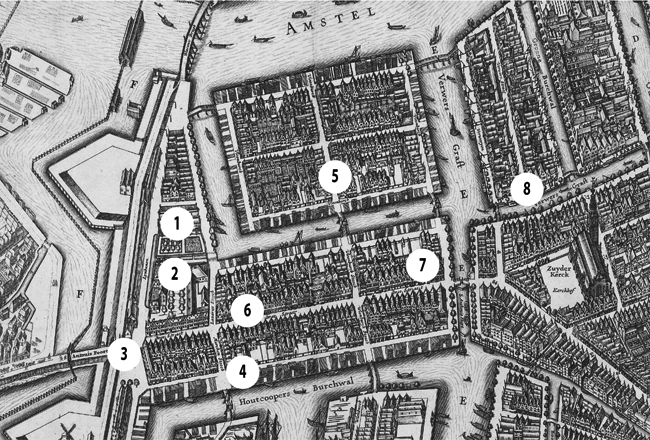

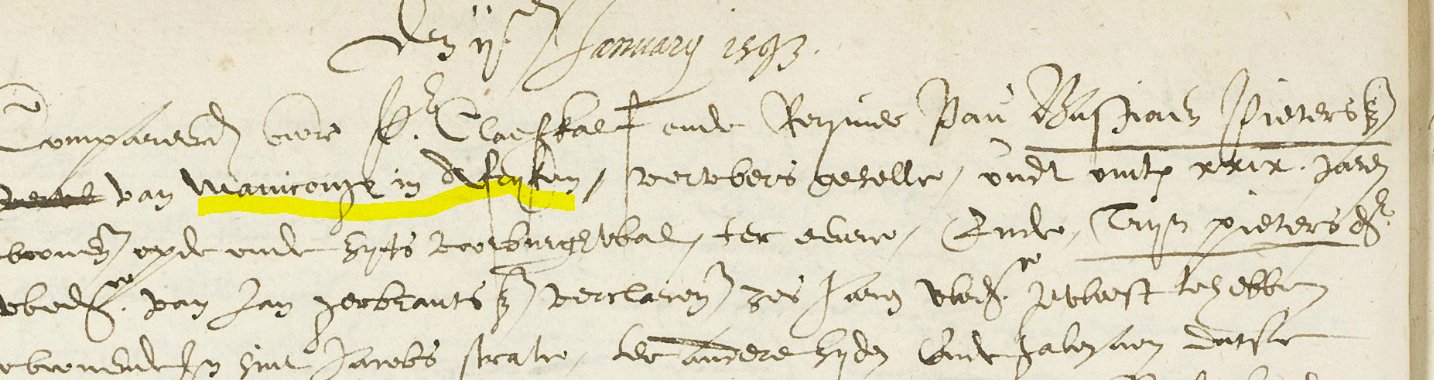

Wanneer de eerste Afrikaan of Aziaat zich in Amsterdam vestigde is natuurlijk moeilijk vast te stellen. Maar de gedocumenteerde aanwezigheid van zwarte Amsterdammers gaat terug tot de jaren 1590. In januari 1593 trouwde Bastiaen Pietersz van ‘Maniconge in Afryken’ – een rijk dat het huidige Congo en Angola omvat – met de Amsterdamse weduwe Trijn Pieters in de Oude Kerk. Pietersz was een verversgezel en werkte dus in de lakenindustrie. Vrijwel zeker was hij een vrije man. In 1594 werd hun dochter Madelen gedoopt in de Nieuwe Kerk op de Dam, misschien wel het eerste Afro-Europese meisje dat geboren werd in Amsterdam. Dit voorbeeld laat zien dat de Afrikaanse aanwezigheid in Amsterdam verder teruggaat dan de eerste gedocumenteerde Amsterdamse slavenhandels reis, namelijk die van het schip Fortuijn dat in 1596 vertrok.

Tegelijkertijd kwamen vanaf het begin van de zeventiende eeuw mensen in slavernij in Amsterdam terecht. De eerste slaafgemaakten kwamen waarschijnlijk mee met Sefardische migranten uit Spanje en Portugal Slavernij was een veelvoorkomend verschijnsel op het Iberisch schiereiland. Zo was in Lissabon rond 1600 ten minste tien procent van de bevolking van Afrikaanse afkomst. Sommige Sefardische families namen slaafgemaakte bedienden mee naar Amsterdam. Op de Portugese begraafplaats Beth Haim werd een aparte plek aangewezen als begraafplaats voor escravos (slaven), criados (bedienden) en moças (dienstmeisjes) die wel joods, maar niet Portugees waren. In de zeventiende-eeuwse begraafboeken zijn verschillende mensen van Afrikaanse afkomst te vinden die op deze aparte plek werden begraven. De term ‘slaaf ’ werd slechts tweemaal genoteerd: ‘Op 28 [september 1617] werd een slavin van Abraham Aboaf begraven, achter de slavin van David Netto’, later spreekt men van negros of mulatos. Andere joden van kleur werden op een reguliere plek op de begraafplaats begraven, zoals de ‘mulatte vrouw van de mulat Trombeta’ in 1620, en in 1629 de inmiddels beroemde Elieser, de zwarte bediende van Paulo de Pina. Die laatste kwam naast een slavenhandelaar te liggen.

Wetgeving over slavernij in Amsterdam

Met de komst van bedienden in slavernij werd de kwestie van slavernij in Amsterdam actueel. Formeel was slavernij al sinds de middeleeuwen niet toegestaan in de stad. In de boeken met ‘Keuren en Costumen’ van Amsterdam is vanaf 1644 een bepaling over slavernij opgenomen. Deze Amsterdamse bepaling was een letterlijke kopie van een Antwerpse die teruggaat tot in de zestiende eeuw. ‘Van den Staet ende conditie van persoonen’ de bepaling opgenomen dat: ‘Binnen der Stadt van Amstelredamme ende hare vrijheydt, zijn alle menschen vrij, ende gene Slaven.’ Een duidelijke bepaling waarin werd aangegeven dat de stad officieel geen slavernij erkende en dat ieder mens in Amsterdam als vrij persoon gezien moest worden. Het tweede artikel bepaalde hoe men die vrijheid kon opeisen: ‘Item alle slaven, die binnen deser Stede ende haere vryheyt komen ofte gebracht worden; zijn vrij ende buyten de macht ende authoriteyt van haer Meesters, ende Vrouwen; ende by soo verre haere Meesters ende Vrouwen de selve als slaven wilden houden, ende tegens haeren danck doen dienen, vermogen de selve persoonen haere voorsz. Meester ende Vrouwen voor den Gerechte deser Stede te doen dagen, ende hen aldaer rechtelyck vry te doen verklaren.’4 Het was dus mogelijk om de vrijheid te verkrijgen, maar dat vroeg wel wat van degene die in slavernij gehouden werd. Ten eerste moest je op de hoogte zijn van de wetgeving. Ten tweede moest je de (fysieke) mogelijkheid hebben om degene die jou als slaaf hield voor het gerecht te dagen. Ten derde moest je een plek hebben om naartoe te gaan nadat je bevrijd zou zijn. Hierdoor kon slavernij in de praktijk wel degelijk voorkomen.

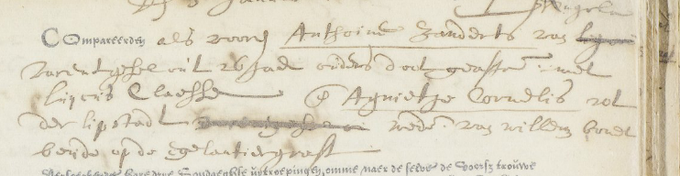

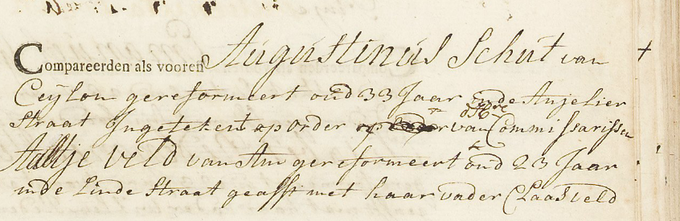

Juist in deze periode kwamen steeds meer mensen uit het Atlantisch gebied en Azië de stad binnen. Vrije zeelieden, maar ook mensen in slavernij. Uit Afrika, Azië en, vanaf de verovering tot aan het verlies van ‘Nieuw Holland’ door de WIC, vooral uit Brazilië. De latere admiraal Jan van Galen ‘gaf ’ zijn vrouw Hillegonda Pieters in de jaren 1620 de ‘morin’ Maria. In 1638 kwam Hans Willem Louissen met vrouw, twee dochters en twee ‘moulaten’ met het schip De Regenboge uit Brazilië. In 1639 vertrok Joan Roiz Machado met zijn vrouw en een zwarte slaafgemaakte man met het schip Barcque Longe eveneens uit Brazilië. In 1642 schonken Simeon Correa en zijn vrouw Maria da Costa Caminha in Amsterdam de vrijheid aan de zwarte vrouw Zabelinha en haar kinderen. In het kerkje van Sloterdijk trouwde op 27 oktober 1652 slaafgemaakte Jacob van ‘Bangalen’ met Susanna van ‘Gujarati’. Na de voltrekking van het huwelijk werd het echtpaar teruggezonden naar Azië. Zij waren naar Amsterdam meegenomen door Jan van Teylingen, commandeur van de VOC-handelspost Suratte in India.

In de praktijk verliet een deel van de bedienden, al dan niet met toestemming, hun ‘meesters’. In de jaren 1630 leefden dan ook diverse vrije zwarte families in de omgeving van Vlooienburg en de Jodenbreestraat. Uit onderzoek is gebleken dat tussen 1630 en 1665 ongeveer honderd mensen van Afrikaanse afkomst trouwden in Amsterdam; deze mensen woonden vrijwel allemaal bij elkaar in de buurt.6 Uit de schaarse documenten blijkt dat deze mensen elkaar goed kenden, en met elkaar optrokken. Regelmatig trouwden in Amsterdam aanwezige zwarte vrouwen met zwarte zeemannen die meestal via Brazilië in Amsterdam terechtkwamen. Deze gemeenschap vormde waarschijnlijk het vangnet waardoor mensen als Juliana uit slavernij konden vluchten.

Toename van slaafgemaakten uit Oost en West

De situatie veranderde met de vestiging van verschillende plantagekolonien in Zuid-Amerika, Suriname, Berbice en Demerary. Deze koloniën waren zoals elders in deze bundel is te lezen, vrijwel volledig gebaseerd op de arbeid van tot slaaf gemaakte Afrikanen, en in mindere mate Inheemsen. Een klein deel van deze mensen zou ooit in Amsterdam of elders in de Republiek terechtkomen. Toch reisden plantage-eigenaren steeds vaker uit de plantagekoloniën naar de Republiek, voor zaken of om zich daar permanent te vestigen, waarbij zij vaak slaafgemaakte bedienden meenamen. In de loop van de achttiende eeuw nam de komst van slaafgemaakten uit met name Suriname dan ook flink toe. De Surinaamse gouverneursjournalen geven een indruk van het komen en gaan van plantage-eigenaren en anderen met hun slaafgemaakte bedienden. In de loop van de achttiende en negentiende eeuw zijn honderden slaafgemaakten uit Suriname voor korte of langere tijd in de Republiek terechtgekomen.

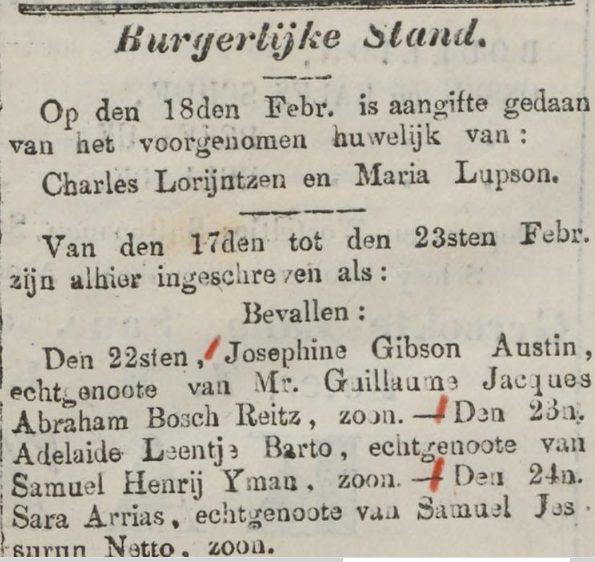

Een voorbeeld uit 1769 geeft een indruk van de omvang van dit fenomeen. Op 1 mei 1769 vertrokken vier schepen uit Paramaribo naar Amsterdam, de Spion, de Jonge Elias, de Johan Coenraad en de Anna Maria Magdalena. Onder de 33 passagiers waren acht slaafgemaakten, Princes en Tamra, de jongen Turk, de jongen Hazard, de meisjes Diana, Porta en Venus en de jongen September. Jaarlijks vertrokken tientallen schepen, en op vrijwel elk schip dat in de Republiek aankwam, waren slaafgemaakten aanwezig. Velen gingen na enige tijd weer terug naar Suriname zonder dat er iets aan hun juridische status veranderd was. Anderen bleven in de Republiek tot aan hun dood, zoals Susanna Dumion, die door de weduwe Susanne l’Espinasse werd meegenomen naar Amsterdam. Dumion wordt door L’Espinasse in haar in Amsterdam opgemaakte testament ‘slavin of dienstmaagd’ genoemd, bij overlijden van L’Espinasse zou Dumion de vrijheid en een toelage van 4 gulden per week worden toegekend. Op 28 mei 1784 liet Dumion zelf een testament opmaken. Uiteindelijk zou Susanna Dumion op 12 november 1818 op 105-jarige leeftijd overlijden in Haarlem, volgens de overlijdensakte liet zij geen vaste goederen na. Andere slaafgemaakten werden in Amsterdam, na kortere of langere tijd, formeel vrijgemaakt door hun eigenaren. Een voorbeeld is Juan Francisco Ado, die in 1731 in Amsterdam arriveerde met Anna Levina Leendertsz, vrouw van de voormalige gouverneur van Curaçao, en oud-schepen van Amsterdam Jan Noach du Fay. Al voor vertrek uit Curaçao was afgesproken dat als de ‘slaaff haar […] behoorlijk mochte dienen en oppassen geduurende de reijse’, hij in de Republiek zijn vrijheid zou krijgen. Formele vrijmakingen hadden meestal te maken met een geplande reis naar het buitenland, meestal terug naar de kolonie, in het geval van Ado terug naar Curaçao. Terwijl in Suriname steeds meer slaafgemaakten het oerwoud in vluchtten om in vrijheid te kunnen leven, hadden de bewoners van de relatief kleine Caribische eilanden als Curaçao minder mogelijkheden. Regelmatig probeerde slaafgemaakten als verstekeling te vluchten, ook naar de Republiek. Lang niet altijd was dit succesvol en dan werden verstekelingen uiteindelijk vaak teruggestuurd. Zoals Paap die in Axim werd geboren en in Curaçao als slaaf werd verkocht. In 1734 ging hij als verstekeling aan boord van het schip Werkendam richting Amsterdam. Hij wilde doorreizen naar Afrika, maar werd na een beslissing van de Staten-Generaal teruggestuurd naar Curaçao.

De viering van de Pesachmaaltijd Bernard Picart , 1725 (Amsterdam Museum)

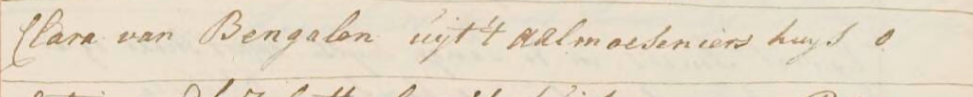

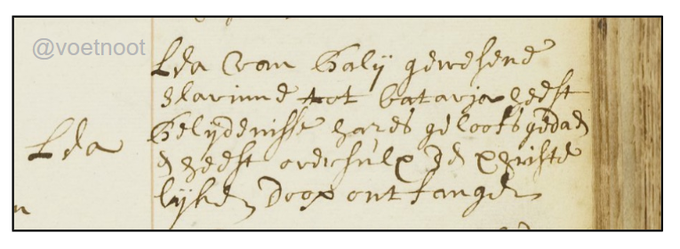

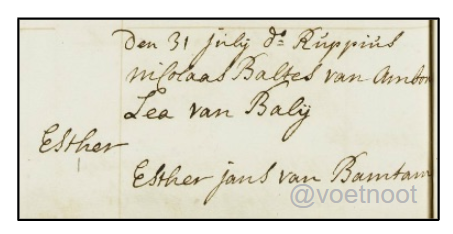

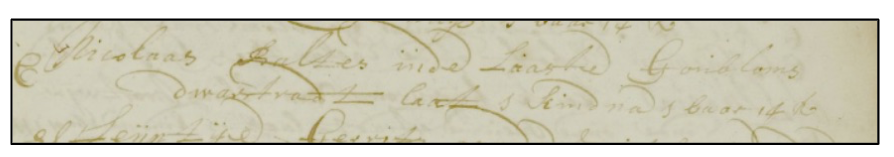

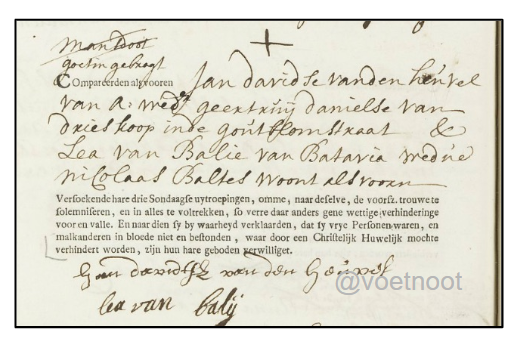

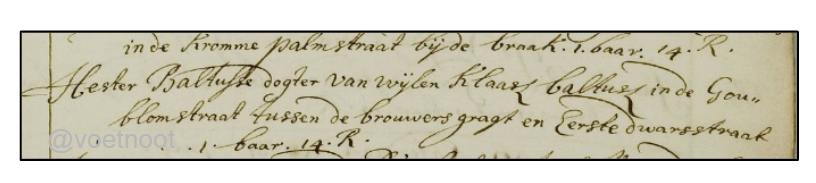

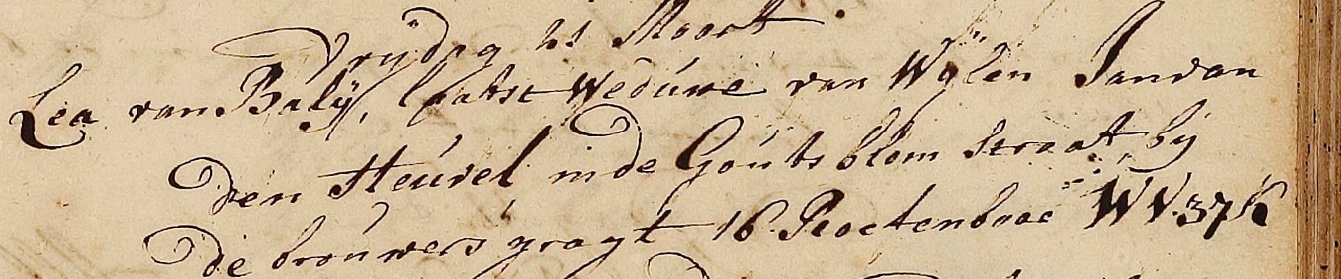

De VOC probeerde de komst van slaafgemaakten naar de Republiek vanuit Azië zoveel mogelijk te beperken. Repatriërende VOC-dienaren moesten meegenomen slaafgemaakte bedienden in principe achterlaten op de Kaap, tenzij zij uitdrukkelijk toestemming hadden om mensen mee te nemen. Toch kwamen veel Aziatische mannen en vrouwen met een achtergrond in slavernij in de loop van de zeventiende, achttiende en negentiende eeuw in Amsterdam terecht. In de bronnen worden zij meestal ‘gewesene slavinnen’ genoemd. Thomas Matroos en zijn vrouw Maria de Grave lieten op 8 november 1729 bij een notaris vastleggen dat hun ‘geweesene Slavinne, die zij uijt India herwaarts met haar hebben overgebragt, genaamt Sara van Java, bij de langst levende zal blijven woonen tot haar dood toe’. Bij overlijdenvan Matroos dienden de erfgenamen Sara in huis te nemen of tot aanhaar dood een jaarlijkse toelage van f. 150,- te betalen. Op 15 mei 1737 liet Calistrevan Amboina (Ambon) bij dezelfde notaris haar eigen testament op- maken, ook zij werd een ‘geweesene slavinne’ genoemd. Zij was naar deRepubliek meegenomen, door de vanuit Batavia repatriërende VOC-opperkoopmanJan Elsevier en zijn vrouw Ida van der Schuur. Op 21 december1691 werd ‘Lea van Balij gewesene slavinne tot Batavia’ in de Westerkerk gedoopt.Ze woonde bij Ida Castelijn op de Keizersgracht en was waarschijnlijkmeegenomen door Ida Castelijn en Jan Parvé, de admiraal van een retourvlootin 1690. De rest van haar leven bleef Lea van Balij in Amsterdamen trouwde in 1708 met Nicolaas Baltus van Ambon (Molukken).

Juridisch verzet en formalisering

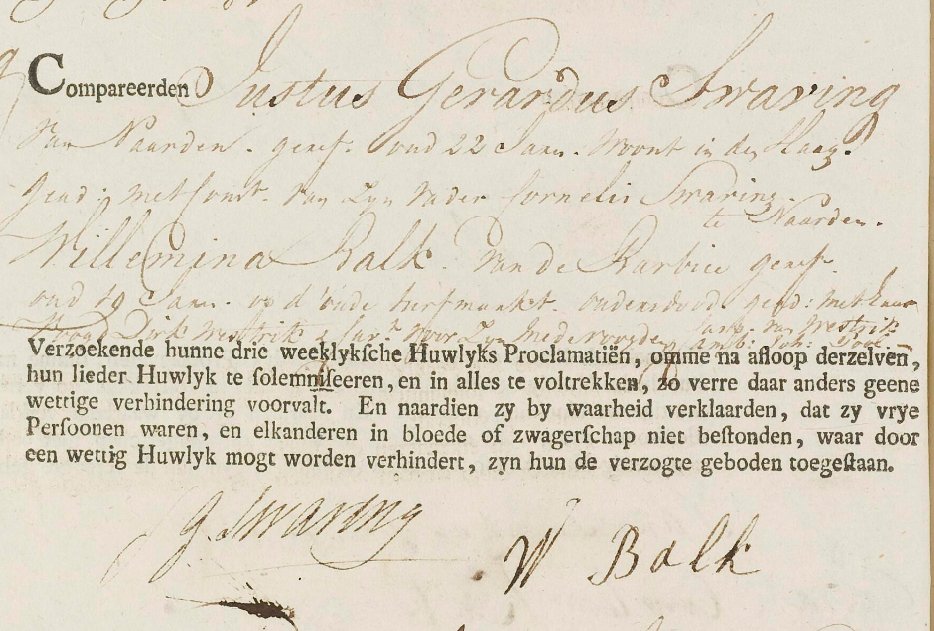

Tot diep in de achttiende eeuw veranderde meestal niets aan de status van slaafgemaakten: zij bleven slaven wanneer zij na een verblijf in Amsterdam terugkeerden naar Suriname of andere kolonies. Totdat Marijtje Criool en haar dochter Jacoba Leilad, beiden als slaafgemaakten naar de Republiek gebracht, in 1771 bij de Staten-Generaal om vrijbrieven vroegen om daarmee als vrije mensen naar Suriname te kunnen vertrekken. De Staten-Generaal besloten, gebaseerd op de oude wetgeving dat de Republiek geen slavernij kende, dat vrijbrieven niet nodig waren, omdat zij vanwege hun aanwezigheid op ‘vrije grond’ automatisch vrij waren geworden. Dat hier direct gebruik van werd gemaakt door andere slaafgemaakten blijkt wel uit het verhaal van Adriaan Isaak Koopman. Koopman was als Fortuin, de slaafgemaakte bediende van Reinier du Plessis, in 1772 in Amsterdam aangekomen. In Amsterdam wilde hij zich laten dopen in de hervormde kerk. Du Plessis wilde daar geen toestemming voor geven, waarna Fortuyn zich op het plakkaat van 1771 beriep.

De beslissing van de Staten-Generaal leidde tot onrust onder de planters in Suriname en de investeerders in Amsterdam. De investeerders in Amsterdam maakten zich druk om het kapitaalverlies. Om hen tegemoet te komen, werd de regelgeving door de Staten-Generaal aangepast. In 1776 werd bepaald dat slaafgemaakten die in de Republiek aankwamen niet automatisch vrij werden, maar pas na een halfjaar, met de mogelijkheid tot verlenging van nog een halfjaar. Als de slaafgemaakte na dat jaar nog niet was teruggestuurd naar Suriname werd hij automatisch vrij, ook bij terugkeer naar de kolonie. Maar zelfs daarna werd dit nog af en toe met succes betwist door slaveneigenaren.

Conclusie

Hierboven is aan de hand van voorbeelden de ontwikkeling geschetst van Aziatische en Atlantische migratie naar Amsterdam gedurende de zeventiende en achttiende eeuw. Gedurende de hele periode van slavernij leefden Aziatische en Atlantische migranten in Amsterdam, al dan niet met een achtergrond in slavernij. Een deel van hen leefde in vrijheid, waaronder een kleine zwarte gemeenschap in de zeventiende eeuw in de omgeving van de Jodenbreestraat. Het oude van vrijheidslievende principes getuigende plakkaat werd nooit door autoriteiten actief gehandhaafd, waardoor slavernij in de praktijk bestond. Het plakkaat bood voor sommige naar Amsterdam gemigreerde slaafgemaakten wel een mogelijkheid om hun vrijheid op te eisen.

In officiële documenten werden voormalige slaafgemaakten uit Azië in de Republiek ‘gewesene slaven’ genoemd. Tegelijkertijd kwamen in de loop van de achttiende eeuw honderden slaafgemaakten uit de Guyana’s voor kortere tijd naar Amsterdam. Aan hun juridische status veranderde meestal niets en zij bleven slaven. Dit werd in de jaren 1770 door een aantal slaafgemaakten succesvol aangevochten, waardoor slaven op basis van een bezoek aan de Republiek vrij konden worden verklaard. Maar deze maas in de wet werd in 1776 gedicht om voorrang te geven aan de belangen van slavenhouders en in slavernij investerende Amsterdammers.

Mark Ponte, ‘Tussen slavernij en vrijheid’ in: Pepijn Brandom e.a., De slavernij in Oost en West. Het Amsterdam onderzoek (Spectrum; Amsterdam 2020) 248-256.